- Home

- Robert Paston

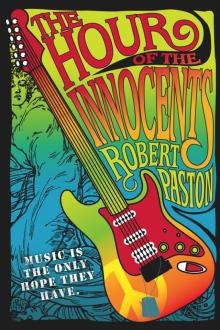

The Hour of the Innocents

The Hour of the Innocents Read online

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you without Digital Rights Management software (DRM) applied so that you can enjoy reading it on your personal devices. This e-book is for your personal use only. You may not print or post this e-book, or make this e-book publicly available in any way. You may not copy, reproduce, or upload this e-book, other than to read it on one of your personal devices.

Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the author’s copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

To my wife, whose taste in music has improved since high school;

to my brother, who got all the musical talent;

and to my co-conspirators in Leather Witch: It was punk rock a decade too soon.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Special thanks to Bob Gleason, masterful editor and former steel worker, who “got it.”

CONTENTS

Title Page

Copyright Notice

Dedication

Acknowledgments

Epigraph

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Author’s Note

About the Author

Copyright

After-comers cannot guess the beauty been.

—GERARD MANLEY HOPKINS, “Binsey Poplars”

ONE

The Army gave him a last fuck-you haircut on the way out. It made him look out of place even in the American Legion.

The vets who returned that year were different. I witnessed the change from the bandstand, week after week, from midnight on Saturday until three on Sunday morning. Their predecessors had come home from Nam, drained their GI savings to buy a Chevy Super Sport or a Plymouth Barracuda, and plunged into doomed marriages with high school sweethearts. Those former soldiers and Marines kept their hair as short as their tempers, got union cards through family connections, and shrugged off their years in uniform. When they came out to get drunk, the music was just background noise.

The Tet Offensive divided the past from the future. The vets who came home after that were as apt to buy a Harley as an Olds 442. They grew their hair—not hippie long, but defiant. Drugs arrived. And the new returnees asked us to play different songs. Instead of “Louie Louie,” they wanted numbers from the Doors or the Stones or Cream. The fights that spilled outside onto the sidewalk continued, but these weren’t the old collisions of tomcat pride. These fights were sullen. As if the vets were following orders they hated.

Matty Tomczik looked like a barroom brawler when he walked in. He was defensive-lineman big, and that last military scalping had cut so close to his skull, you couldn’t be sure of the color of his hair. With a wide Polish face and a fist-stopper nose, he came across as one more dumb-ass coalcracker unsure of what to do with his limbs in public. Later, I learned that what I read as oafishness was a shyness so deep, it crippled him around women.

Matty was surrounded by women that night. Angela, the wife of our bass player and front man, led Matty in with a pack of her giggling friends, beauticians and candy-stripe nurses who recently had discovered marijuana. Angela’s long blond hair shone. A year before, when I first joined the band, she had worn a beehive and toreador pants. Now she had a San Francisco look, copied from magazines and complete with purple-lensed glasses she didn’t need.

Working through the rote licks of “Light My Fire,” I watched my enemy invade my world. The party’s arrival at the side of the bar was a sloppy, happy explosion, with Angela posing for the crowd and waving to Frankie. Angela was the star of her own show and the perfect wife for Frankie, who’d shortened his last name, Starkovich, to Star for his stage persona.

The volume from our amplifiers reduced Angela’s entrance with Matty to a pantomime: “Vestals Leading a Minotaur to the Sacrificial Altar.” The song’s roller-coaster organ riff kicked in one last time—Ray Manzarek’s four bars of genius—and we wrapped up the song to spotty applause. Someone shouted, “Heavy, man!” But it hadn’t been “heavy.” It was plastic, the musical version of monkey-see, monkey-do. I hated playing other people’s music note for note. But that was the price to be able to play at all.

I had fantasized about playing a number that would let me show off when Matty the Legend appeared, something that would let me go beyond aping parts from somebody else’s record. I wanted to fire off a guitar solo that would shut him down from the start. I had pushed Frankie to announce “The Stumble,” so I could riff on Peter Green’s version from A Hard Road, but he blew me off with, “Later, man. That’s not first-set stuff.”

Now it was too late. The room’s attention deserted us for the new arrivals. Angela and her gang got things going just by filtering through the crowd in search of a table. Attached or stag, the males were interested. With their paisley fabrics, beads, and scarves trailing over tight bell-bottom jeans, those girls promised sex that would soar beyond the typical backseat muggings of our world.

It was an illusion, of course. They were the same girls from Shenandoah and Frackville as ever, dressed up for a costume party. They were still as hard as anthracite.

Trapped under teased hair and with an extra blouse button undone for Saturday night, the other women in the room were less welcoming than their dates. Angela was a threat. And her girlfriends, judged by peers, were trashy sluts. It amazed me that Angela never got into a fight with another woman, given how she behaved when playing hippie. On the other hand, she still had a reputation from her years at Cardinal Brennan. She was all peace signs now, but Stosh, our drummer, claimed that Angela’s preferred move in a catfight had been to grab just enough hair from the other girl’s temple to rip out a patch of roots the size of a quarter.

She floated across the dance floor, towing Matty the Minotaur. His body seemed reluctant, and the expression on his face was dumb bewilderment. But his eyes were already fixed on my guitar.

I wouldn’t have minded if he hadn’t come home from Vietnam.

* * *

“All right, okay,” a preening Frankie told the microphone. Sweat had begun to darken his red hair and he braced his fists on his hips the way Mick Jagger would. When I auditioned for the band the year before, Frankie had still worn a ducktail. Now his hair inched below his collar, long enough to draw calls of, “Yo, faggot!” when he walked down a coal-town street.

“Ladeeez and gentlemen…,” Frankie went on, “we’ve got something special for you this evening … I mean something really special … just back from his all-expenses-paid vacation in Vietnam … on his first night home … our old guitarist from the days of yore, when the Destroyerz were known as the Famous Flames … Matty Tomczik.”

I was seated in the audience by then, down in the thick of the cigarette smoke and beer stink. It pleased me when the response to Frankie’s announcement didn’t amount to much. The crowd didn’t remember Matty.

“‘Purple Haze,’” somebody shouted from the bar. “Play some Hendrix, man.”

I looked past the couples on the dance floor, most of them women facing other women. Matty silently tested the fret spacing on my Les Paul. His

hands were the size of baseball gloves, with swollen-looking fingers, as if he had worked a lifetime in the mines. Hanging from his big shoulders, my guitar looked like a toy.

“‘Purple Haze,’” the guy at the bar yelled again. He was one of those characters who were always around, small and scruffy, with a ragged mustache and wire-rims, one of the drunks who pretended to have drug connections. But I was grateful for his taste in music. I could never get the intro to “Purple Haze” just right when we played it, couldn’t quite hear the odd combination of notes. Jimi Hendrix heard things others didn’t and played things others couldn’t. Matty had been away for two years, much of that time in Vietnam. He’d be stumped.

I needed Matty to disappoint his old friends, his schoolmates from up the line who had ducked the draft. It wasn’t just that I was sick of hearing about what a great guitar player he was. I was scared. I had been with the Destroyerz for almost a year, the only replacement guitarist who worked out for them. We’d built a following. People even knew some of the songs I’d written myself and asked for one every so often. Now Matty was back, and although no one had said a word about it, I knew I was on my way out if he had any chops left.

I longed to smash their closed circle. The other members of the group were all older than me, in their early to mid twenties, and they shared that secretiveness, the inside-joke attitude, that people from the Hunkie towns north of the mountain used to exclude outsiders. And I was from Pottsville, the county seat, which passed for civilization. To them, I was a born enemy, with a name that wasn’t from Poland or parts east. After a year of playing gigs two or three nights a week, with practice sessions sandwiched in between, I was still shut out of every serious discussion among my three band-mates. I was just hired help. In a damned good band. A band that could go places, if Tooker got his act together on the keyboards. And I wanted to go places.

Up on the compact stage, Stosh leaned forward over his drum kit, combing the sweat from his mustache with his fingers and listening as Frankie conferred with Matty and Tooker away from the mikes. Frankie fingered a few bass notes, then stopped in the middle of a riff. I couldn’t hear anything they said. Matty shrugged. Frankie leaned toward him, speaking, gesturing. Matty shrugged again and Frankie turned back to the microphone.

“All right! This one’s for all you Hendrix fans out there.…”

Stosh laid down the tempo with his drumsticks and Matty took it away. He nailed the opening. As if he’d been playing Hendrix from the cradle.

Frankie edged his Fender bass up against the mike stand and shouted, “Purple haze … all in my brain…”

Matty curled the notes of the solo, hitting every microtone. He stood still, feet apart, eyes closed, head nodding just a few inches from the low ceiling. His fingers were dancing elephants. But they danced.

Matty shouted across the stage, and instead of returning to the vocal, Frankie and Stosh kept the bass and drums going, while Tooker—who’d been bluffing an organ part—dropped out. Matty just took off. Riffing wildly, beautifully, humiliatingly. Making his own music. Going to places that were Hendrix but weren’t. As if Matty had merged with the wild man on the LPs.

Musicians are masters at rationalizing away a rival’s talent, but Matty was too good. I sat there, alone at a side table, burning. His playing was brutal and melodic, dazzling, just pouring out of him. I could feel an electric change in the room. Even the serious drinkers knew something was happening. Every soul in that scuzzy, crowded Legion hall stopped and listened.

I hated it.

Matty didn’t drag it out too long. At the perfect moment, he returned to the familiar riffs and Frankie howled the song to its conclusion, slapping his bass and rolling his shoulders, as dramatic as Matty was solemn.

The applause seemed almost as loud as the music had been.

It wasn’t going to be one song and done, either. Matty meant to keep on playing. And I’d just go on sitting. I felt as if every other soul in the room knew that I was about to get the boot. All the hangers-on who wanted to talk about guitarists and groups with me, who begged me to get stoned with them, who wanted something from me they couldn’t explain … they had Matty now. And Matty was one of their own.

After a round of dap-slaps onstage, heads came together for another conference about what to play next. Angela dropped into the chair beside mine, tossing her Indian scarf back over a shoulder. It was stifling in the room, but there wasn’t one bead of sweat on her.

“He’s good, ain’t?” she said. “That Matty?” Smiling her all-purpose Angela smile. Beneath an embroidered black vest, a purple jersey gripped her breasts.

“Yeah,” I said. Desperate to sound unfazed. “He’s good.”

Tooker hit a D on his organ and Matty tuned my guitar.

“And you’re sitting here thinking he’s better than you, ain’t?”

“He’s older,” I said quickly.

“You think you’ll ever be that good? You should hear him when he doesn’t have a case of beer in him.”

I opened my mouth to speak, then realized she was teasing me. Angela had a brilliant grasp of the weak points of her victims.

“‘Wipe Out!’” somebody yelled. One of the old-timers, a shot-and-a-beer guy.

Angela leaned closer. She smelled of marijuana and Avon perfume. Up close, her features were one edge too sharp for beauty. A north-of-the-mountain girl trying to put it together, she was one of those blondes who look great from ten feet away.

“You didn’t call Joyce. All week.”

“We didn’t hit it off.”

“She thinks you did.”

“We aren’t a good match.”

“You balled her.”

I shrugged. “I’m not sure who balled who.”

Her smile grew harder. “You always got to make out like you’re so grown-up and hip. You’re just a kid, Bark. And everybody knows it. What are you, one year out of high school? Playing in a band with the big boys. Like you’re Eric Clapton or something. And you screw one of my best friends and don’t even call her? I thought you rich kids were raised up to be gentlemen?”

“We’re not rich.”

I waited for her to say something mean about my father killing himself.

Instead, she told me, “I should pour this fucking beer over your head, you know that? For how you treated Joyce. She’s not one of those college tramps of yours.” Her inscrutable-Angela smile returned and she tapped a cigarette out of a flip-top box. “And stop looking at my tits.” She lit up with a crimson Zippo, sucked in the smoke, blew it toward me, and said, “They’re not my best feature, anyway.”

Rather than dumping her beer over my head, she reached out and ruffled my hair, which was worse. “You’re such a little snot,” she told me. “Reading poetry to her and all. To Joyce, for Christ’s sake. She couldn’t understand half the words. You had her wondering if you were ever going to shut up.” Stubbing out the cigarette she’d only begun to smoke, Angela rose. “She had a good time, even if you didn’t. You’d better call her, before she tells her boyfriend.”

Laughing, Frankie stepped back to the lead mike. “Okay, folks. Let’s set the time machine for 1963!”

They really did play “Wipe Out,” the ultimate un-hip surf-guitar tune, a staple from their old days together. Schuylkill County’s answer to Keith Moon, Stosh hammed up the drum break. When they came back to the guitar line, Matty took off again, playing speed-freak riffs that took the main theme to places Coltrane might have found if he’d played electric guitar. Matty’s baseball-glove fingers leapt out of each other’s way as they bent the strings. He turned that barfly instrumental into a psychedelic march, playing lines so fast and crowded that it seemed he’d have to break off to catch up with himself. He snagged the guitar’s volume nob with his little finger and cranked it up.

The crowd started to howl. Half of them were standing. I stood, too.

Five minutes earlier, I’d been anxious for him to hand my guitar back to me, to let me play out

the set. Now I wanted him to keep going, at least until the next break. Even on my best night, I couldn’t rival him. I couldn’t come close. I’d never heard anyone who wasn’t already famous play so well. I didn’t want to follow him without an interval; fifteen minutes to let people forget.

He played the way I dreamed of playing.

When the applause died down, I shouted a request: “‘Goin’ Home!’”

With Frankie showboating on the vocal and an extended solo from Matty, that one song would finish off the set.

* * *

Matty came down and took the chair that Angela had warmed. She was up on the stage with Frankie, talking to him as he toweled off.

“Thanks for letting me play your ax,” Matty said. He spoke slowly, as if he found words hard to form.

“No big deal, man.”

The guy who’d called for “Purple Haze” came up. Looking at Matty, he said, “Wow, man. Like that’s all I can say, you know? Wow. That was some heavy shit. It was like Jimi was right in this room.”

Matty looked down at the wet rings on the table.

“Welcome home, man,” the intruder went on. “I been to Nam, too. FTA.”

Matty nodded but didn’t raise his eyes.

Stosh turned up with two bottles of beer and edged the fan aside. “Band talk,” Stosh told him.

“That’s cool. I’m cool with that. Just play more Hendrix, man.” He walked away.

After handing Matty a Rolling Rock, Stosh sat down and tugged his shirt away from his chest: red satin, with mother-of-pearl buttons. “Cripes, it’s hot,” he said. Black hair clung to his neck and gleamed with sweat.

“They’re too cheap to turn on the air conditioners,” I said.

But Stosh was talking to Matty, not to me. “This is just June. Wait until August. You never played a hellhole like this. It gets like a locker room nobody cleans.”

Matty swallowed some beer and turned to me. “Frankie says you write songs.”

The Hour of the Innocents

The Hour of the Innocents