- Home

- Robert Paston

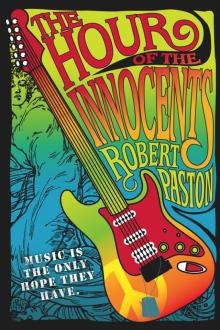

The Hour of the Innocents Page 23

The Hour of the Innocents Read online

Page 23

“I always think about the group. I write for the group.”

“But let’s just see what you can do for Frankie, all right? I mean, he’s your meal ticket, isn’t he? Of course, Matthew’s a superb guitarist. And Stosh could find work as a session man any time he wanted it, I could put him into any studio in Manhattan. But your average listener … that person identifies with the voice, that’s all that he or she really hears. And I want you all to be thinking in terms of careers, not just one album that nobody buys and nobody ever hears. This can’t just be about somebody’s ego. Where do you want to be ten years from now? I mean, you take Frankie here. He could be another Tom Jones.”

I laughed out loud.

No one else did. Of course, they were busy wrestling their lobsters to a gruesome standoff.

“Don’t you have faith in Frankie’s talent?” Luegner asked me.

“Frankie’s a great front man. In a great band.”

“But that’s my point, Will. Frankie’s willing to sacrifice a starring role, to submerge his talent in the group … for the benefit of the rest of you. He could be a solo artist any time he chose.” Luegner smiled. “Maybe trim his hair a little bit. But he could have a thirty-year career. Longer. Do you really think the kind of music you play is going to last that long?”

“It’s doing okay right now.” I didn’t know how to respond effectively. I saw what he was doing, the way he was cutting me out of the pack, making me the scapegoat. He and Frankie must have been having some long and interesting talks. But I just couldn’t muster the words to fight back. And I was still reeling from being the weak link in the studio.

“I’ve seen musical fashions come and go, Will,” Luegner told me. “They just come and go. Only the strong survive. Now, maybe all of this is just a hobby for you—I understand you’re in college, is that right? But for your friends here … this could be a lifelong career, they’re at a turning point. I need you to think of them.”

“Your lobster’s getting cold,” I said.

He waved that away, too. “You boys are more important to me than food. Matthew, I see you’re already finished. May I offer you one of my tails? I’m really not hungry, to tell you the truth. I’m in here so often I get tired of it.”

“Why are you interested in us at all, if you just want to change us?” I demanded.

“Who said anything about changing you? You’ve got a great band. I can’t wait for your first album, Will. I’d love to have another gold record on my office wall. But I want that album to be the first of many. On a reputable label. I want all of you to be thinking three, four, five albums from now. You want to write your college-boy lyrics now, that’s fine. That’s the Zeitgeist, I understand that. Same with the music, those hammers-of-hell songs of yours. In the longer term, though, Frankie’s voice is much too good for that. Your fellow musicians here are too good for that. They could do anything they wanted. I don’t want the material to obscure their talent.”

“What do you want to make us into? Gary Puckett and the Union Gap?” I turned to my right. “Frankie? Is that what you want? Or do you want to be another Robert Goulet?”

“There’s no need to get argumentative,” Luegner told me. “Nobody here said anything about Robert Goulet. And, to tell you the truth, Frankie’s voice is better than Goulet’s, if you want my opinion. Just give it a little training. You boys like a little dessert? Some coffee for the long drive home? I hate to admit it, but sweets have always been my personal weakness. Listen to me now. Let me tell you what I’m going to do. As a demonstration of how much I believe in you, in all of you. As a show of good faith, I’m going to set up some real-money gigs for you, say, a few good club dates. That’s where the money is, anyway—do you know how much a house band can make in a week in Vegas? Not that we’re talking Vegas just yet. And another thing: I’m not going to take a commission, not for these goodwill gigs. I don’t want you to sign anything, either—I wouldn’t even let you. I need to show you what I can do for you. No pie-in-the-sky recording contract promises. All that will come in time. Let me start by putting a little serious money in your pockets.”

“That’s exactly what Milt Ehrlich said you’d pull,” I told him.

He beamed. “See? The man knows me. He knows I get results. Everybody knows Danny Luegner. Now, if you boys think your stomachs are up to it, I highly recommend the cheesecake.”

NINETEEN

Matty finished chewing the bite of hot dog and said, “Don’t turn this into a contest between you and Frankie, Will. He’d break up the band before he’d let you win.”

I stopped my cheeseburger halfway to my mouth. “It’s Luegner who’s trying to drive in a wedge, not me. He wants me out. I mean, that’s pretty clear. He’s the one who wants to break up the band.”

“Look, I don’t like the guy, either.” Matty took a drink of chocolate milk. He was the only grown man I knew who touched the stuff. “And Stosh doesn’t think much of him, I can tell you that. But he’s got a hook in Frankie, he knows what Frankie wants to hear. But you can’t talk to Frankie, Will. You’ve got to let him figure things out on his own.”

“And if he doesn’t figure them out? In time?”

“We just have to wait. And hope, I guess. Let’s see what your contact from Eclecta comes up with. Frankie can be flattered, but he can’t be suckered completely. A firm record deal would trump a couple of club dates. But you have to lay off him for now. Just play along, all right? You attack Luegner and Frankie takes it as a personal attack. And don’t expect us to gang up on him. The band doesn’t work that way. You going to finish your fries?”

I was ill at ease with all of it. With the sudden emergence of Danny Luegner as a factor in our lives. With Matty’s insistence that we meet at the Coney Island, not at my apartment, as if we had to talk on neutral ground. And slush had soaked through my boots on the walk downtown, leaving my socks sopping.

“So … what am I supposed to do? Just watch while Luegner tears the band apart?”

“Let him put up, or shut up. I told you.” Matty glanced at the waitress, who had been a fixture behind the counter for as long as I could remember. Recently, she had dyed her hair blond. Thirty years too late.

“He’ll come through with those club gigs he promised. The guy from Eclecta warned me. It’s his standard setup.”

“Listen to me, Will. I mean it. I want you to listen to me for once. Never let an enemy know you’re nervous. Never show fear. You can act as though you know you’re going to win, or like you don’t care who wins. But never let on that you think there’s a chance you could lose.” He shook his head. “I used to daydream about Coney Island dogs in Nam. But they’re really not that good, to tell you the truth. Fries are okay, though.”

“Matty? What do you want out of all this? Really?”

“To play music. To play good music.”

“And? I mean, you must want more than that?”

He considered the question. I still could not square the big, slow character across the table from me with the superman who had served in Vietnam. Or even with the music that burst out when he held a guitar. Unlike me, he never even seemed to practice seriously. He just played.

“I want,” he said, “people to leave me alone. That’s it, I guess. To play music. And be left alone.”

“But don’t you want to be on albums? Like we always talked about? To have your playing recorded? So it won’t just be lost? Don’t you want more people to hear you?”

He shrugged. “I suppose. Sure. That would be great.” But he was still pondering the basic question. His face grew somber. “We don’t all want the same things, Will. As long as there’s enough overlap, like in the band, things are okay.” He pushed his empty plate away. “I never know how to say things so they come out completely right, I wish I had your way with words. I mean, take Frankie and this Luegner guy. Everybody can see that Frankie’s being selfish, that he’s being a jerk. But look at you and me. We’re selfish, too. I don’t know, maybe

I’m the most selfish of all of us. In his way, I guess Frankie’s just more honest about it.”

“And Stosh?”

“Stosh isn’t selfish. Not like you and me and Frankie. Don’t mix up greed and selfishness. They’re not the same. He’s mostly afraid.”

“You mean because—”

Matty raised a hand. Like a priest about to give a blessing. Or a warning.

“We don’t need to say some things out loud. What I mean is that he’s afraid of being left out. He always was, as long as I’ve known him. He wants to be accepted, to be part of something other people think is important. Frankie wants people to adore him, for every girl on earth to fall in love with him. But Stosh just wants people to like him, to let him be one of the guys.”

“You really don’t care if people like you. Do you?”

“I like it when people like the music I play.”

“But you don’t care if they like you. Do you?” I felt that I had grasped something important, although I had only seen what had been there, in plain sight, from the start.

“I want people to not bother me. I told you.”

“But you risked your life for other people. In Nam.”

“That was my job.”

“That’s not a real answer.”

He shrugged. “Maybe I care what happens to people. To some people. I just don’t care if they like me. I don’t want them to hate me or anything, I don’t mean that. I just want everybody to leave me alone. Doesn’t that make sense to you?”

“You cared about Doc. Didn’t you want him to like you?”

“Doc had a gift. I cared about his gift. And I was responsible for him.”

“What about Angela, then? Don’t you care what she thinks of you?”

He went utterly still for a pair of seconds. Then he told me, “That’s my business. There are things nobody else would understand.”

“Don’t you ever want to just talk? To a friend?”

“No.”

“You care what happens to Angela. I know you do.” Anger surged within me, abrupt and unreasonable. “How in the name of Christ can you let her fall apart? How can all of you just let her fall apart like that? While we all just watch, like it’s some kind of horror movie? How can Frankie do it?”

“She’s Frankie’s wife.”

“That’s no answer.”

Matty looked at me as if I were a new recruit who hadn’t learned a thing. “She’s Frankie’s wife. He’d let her die before he’d give her up.”

“And you’d let her die, too?”

“Angela won’t die.”

“Matty, look at her. She looks like a hag.”

“She doesn’t look like a hag.”

“Then what would you call it?”

“She looks tired.”

“She’s killing herself. For God’s sake.”

He pulled up the drawbridge. “It’s none of your business, Will. It doesn’t concern you and you need to shut your mouth now. I don’t care what might have happened or what didn’t happen. But you’re not part of this, you’re an outsider.” He looked down at the mess on the table, then met my eyes with an expression cleansed by force of will. “Just forget it. Go home and write a song. That Luegner guy was wrong, you know. The things you write will last.”

“Don’t shut me out. Please, Matty.…”

He tried to smile but failed. “There’s nothing more to say about it,” he told me. “Words only make things worse.”

* * *

I didn’t go home to write a song. My mother had extended her stay in Palm Beach, a hint of courtship. Every few days, I had to check on her house, to make sure the furnace was still running and the pipes were okay. From the Coney Island, I walked down to the Necho Allen Hotel and turned up Mahantongo Street. When a woman slipped in the slush in front of the Reading Company offices, I rushed to help her. She regarded my long hair with dread, as if I would seize the opportunity to inject her with a lethal dose of heroin. Sleet pricked my face. I wished I had worn a hat.

By the time I reached my mother’s house, my hair was heavy and my peacoat sodden. With my boots pulled off, my socks squished on the wood floors and the carpets, leaving a trail. I turned up the heat and showered in my father’s bathroom, with the water heater knocking so badly that I could hear it two floors from the basement. Then I foraged for dry clothes among my father’s wardrobe, something I had never done before.

In each of the drawers, the underwear, socks, handkerchiefs, sweaters, and folded shirts had gone undisturbed for two years. The items I selected fit jarringly well.

I laid my jeans over a radiator to dry, then went downstairs in pajamas and a heavy cardigan. The furnace growled, reminding me to top off the coal hopper—which I should have done before taking a shower. But I wasn’t ready to do any chores just yet. I prowled into my father’s study, opened the drapes to admit the gray light, and sat behind his desk. The dust was readily visible, as if I had entered a tomb.

It was a day of firsts. Wearing my father’s clothing, I opened the middle drawer of his desk. Then I went through each of the other drawers. As if I might find answers to questions yet unformed.

Behind the blue box with his Purple Heart from Aachen, he had stashed a copy of The Young Lions. Unable to fathom why he would have hidden the novel, I took it out.

Polaroid photos hid between the pages.

We think we know ourselves, our lovers, our parents. But we know nothing. All we have are the finger paintings we make of them in fantastic, inaccurate colors to suit ourselves.

I slammed the book shut. Then I opened it again.

* * *

Milt Ehrlich called with stunningly good news. He had gotten us on the bottom of a bill at the Fillmore East in Manhattan in early February. A weeknight concert, with up-and-coming groups but no big names, it was an ideal showcase for our music. And going onstage at the Fillmore East was more than just a step toward the dream—it was the dream.

“I cashed in a lot of chips to make this happen,” he told me, “and everybody who matters is going to be there. Don’t let me down.”

* * *

We played Lancelot’s Lair again, as the headline band this time. Despite bad roads, a serious following showed up. From the first song of our first set, the surge of energy between us and the audience was powerful enough to blow out a transformer. We introduced two new originals we intended to record during our next studio session, a slow, bluesy number, “My Name Is Darkness,” and a pedal-to-the-floor rocker, “Knife Point.” Both songs let Frankie run through minidramas behind the mike stand and showcased Matty’s ability to astound mere mortals. Trying to drive home that it was all about the band as a whole for me, I declined to take solos in either song and just filled in the architecture with underscoring riffs or accented the rhythm with jagged chords.

Musically, it may have been the best night we’d had until then. Onstage, everything was magic. On the solos I still merited, I played as well as I had ever done. Matty and I got into a scorching exchange of licks in the middle of “Hideaway.” The crowd was our prisoner.

But there was a price for the emotional intensity. At the end of that first set, I felt so drained that I was almost sick. As if the audience had been drawing my blood, sucking out all my juice. Half in a trance, I meandered back to the tiny dressing room to change my soaking shirt. I couldn’t snap back to reality, couldn’t clear the psychic fumes from my head.

Stosh came in while I was changing.

“Jeez, we played the fuck out of things. Ain’t?”

“It was a good set.”

“Shit, it was more than good. It was great. You were on fire, man.”

“Everybody was.”

“The new songs went down good. I really like that one, ‘Knife Point.’” He played a drum break on the wall with his palms.

Frankie came in. The room was little more than a closet and three was a crowd. “Get to know your buddy,” he said as he rubbed past me. High school locker-

room crap.

“Christ, I wish Angela wasn’t here,” he said. “Why’d she have to come along tonight, of all nights?”

She had been coming to almost every gig of late. She didn’t seem to have much else to do. According to Red, Angela’s doctor had given her a clean bill of health after a couple of shots, but her mental well-being was another matter. She behaved erratically and had started public fights with Frankie while our band was on break at two club gigs. That didn’t win us friends among the owners.

I couldn’t understand how she and Frankie could remain together. After the Christmas Eve trauma, I had expected Angela to move out or give Frankie his walking papers. Instead, they went on living together. When I tried to puzzle it out with Red, she just laughed and said, “What do you think the priest told her to do?”

Frankie pulled off his shirt, treating Stosh and me to a whiff of his armpits. As he bent to his gym bag to choose another stage rag, he told me, “That Joan cunt’s out there waiting for you.”

That snapped me back to full consciousness. My only disappointment of the evening had been that I hadn’t spotted Joan in the crowd. Despite my neglect of her, I had expected her to show up in front of the stage, just as she had on the night we’d first met. My vanity was boundless.

The Hour of the Innocents

The Hour of the Innocents