- Home

- Robert Paston

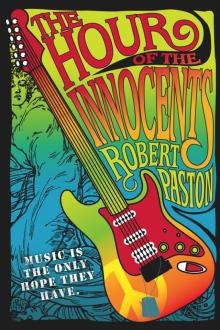

The Hour of the Innocents Page 3

The Hour of the Innocents Read online

Page 3

He glanced toward us, then edged in among the dancers, doing his onstage moves and lip-synching. No one else could have brought it off without looking like a fool.

“He’s such a dickhead,” Angela said.

“For the record, I don’t think Matty’s stupid.”

“You’re a liar.” She leaned against me harder, so I could feel the bone beneath the flesh and smell her breath. “But I forgive you. You know why? Because you’re just a funny kid. Most of the time you don’t even know you’re making it up.”

“What’s your point, Angela?”

“You know I dated Matty? Before Frankie. Not that we were serious or anything.” She laughed. “Matty wouldn’t do nothing the priest hadn’t blessed in writing.” She laughed again, with a bitter edge this time. “That wasn’t a problem with Frankie.”

“I can’t picture you with Matty.”

“Neither could Matty’s mother. Look out for that one. She puts on her poor old babushka act, but she’s a bitch.” Angela rubbed against me, as if feeling a sudden chill. “You know Matty never skips mass on a Sunday morning? Never. I don’t know if he’s scared of God or of that old witch with her pinned-up hair.”

“What about his father? I met him today.”

“That prick. He’s the reason Matty didn’t go to college. Bet you didn’t know that, Mr. Genius. Matty had a scholarship. To study mathematics. He was smarter than the teachers. But his old man shamed him into joining the Army.”

“I thought he was drafted?”

“Matty wouldn’t of ducked out like some people we know. But his old man made him join up.”

“Why?”

“For Matty playing music. His old man wanted him to play football, he had his heart set on it. Matty was supposed to be this big football star. They even redshirted him in sixth grade. It was all his old man ever cared about. And Matty let him down. All Matty wanted all his life was to play music.”

Joey put a Sam & Dave album on the turntable and notched up the volume. “Hold on, I’m comin’…” Meth was going around for the first time, getting people to dance at parties again. Frankie twisted and waved his arms in the center of the pack, facing one girl and then another. The only one he avoided was Joyce, who was still paired off with her biker.

Angela lit a cigarette. “Look at him,” she said.

“How did Matty’s father shame him into joining the Army?”

She smirked. “Ever hear of ‘covering quarters’?”

I shook my head.

With a mocking laugh, Angela said, “No. You wouldn’t of heard of it. I bet nobody in your family ever heard of it. Ask Stosh. Just don’t ask Matty, okay?”

“Okay.”

“Anyways, Matty got these two uncles.” She sucked on her cigarette, then resumed speaking before all the smoke had left her lungs. “One’s a Statie, a real crazy cop. That’s Johnny, the youngest brother. He gets the final say in things, though. Except when the older brother, Tommy, puts one over on both of them. Ever heard of Tommy Tomczik and the Polka Masters?”

“No.”

“They were big up our way. Anyhow, Tommy saw right off that Matty had talent—Matty started out playing the accordion, you know that? You should see the pictures, you’d freak out. This big Polack kid with a red accordion and a bright blue suit with the pants too short. ‘Little Matty, the Wonderful Wizard of the Accordion.’ But Matty wanted to play the guitar worse than anything and couldn’t get no money to buy one—all the money from him playing with the polka band went straight to his old man, that was the deal to get Matty out of football. Well, this smart uncle, Tommy, notices Matty’s real big for his age some ways, but everybody just sees him as a kid. So he’s a ringer for covering quarters and nice Uncle Tommy tells him he can raise the money for a guitar, if he doesn’t go blabbing to his parents or say anything at confession.”

“What’s ‘covering quarters’?”

“Use your imagination. Or ask Stosh.”

On the makeshift dance floor, Joyce hung her arms around the biker’s neck. I caught her looking over at me. And at Angela.

“Anyways,” Angela continued, “there’s this gambling raid on a bar that’s supposed to be closed for the night, it’s like three A.M. or something. Matty’s in the middle of the bust and he’s, like, thirteen or fourteen. There’s not just gambling charges, there’s morals charges, too. Uncle Johnny, the State Trooper, gets his family’s part hushed up quick, but he has to tell Matty’s old man. Who’s got something on the kid after that. Only he doesn’t do nothing with it right away. He just holds it back and doesn’t say nothing for years. And all the while Matty’s terrified his mother’s going to find out.”

She cocked a knee on the sofa. “His old man doesn’t even say nothing when Matty starts playing in rock-and-roll bands. He just waits until that scholarship comes in. Then he lays down the law: Either Matty joins the Army, or his old man tells his mother what he did.” When she laughed, the sound was wrong. “Any other guy would’ve told his old man where to stick it. But Matty was still afraid of his mother finding out.”

“How do you know all this?”

“From Frankie. They used to be best friends.”

“I thought they still were.”

She shook her head. “Not really. Something happened.”

Joey put on Quicksilver Messenger Service and disappeared again. He was the deejay, master of ceremonies, and bulk dope vendor. I never saw him with a girl old enough to expect a cut of the profits.

Angela brought her face closer. “Don’t look down on Matty, Bark. He’s different. He’s a good person.”

Changing speeds, she gave me the full Angela smile and leaned against me hard. “You really do have the hots for me. Ain’t?”

“You’re Frankie’s wife.”

She laughed. “Like that makes a difference. You’re soooo sweet sometimes.”

She gave me a fallen-angel kiss on the cheek. Then she rose. She was just wasted enough for it to take two tries for her to get up from the sofa.

“I got to get Frankie out of here,” she said. “He got work in the morning.”

“Take Joyce with you.” The biker was pawing her in the middle of the room. His friend sat watching them.

“Fuck Joyce,” Angela said.

* * *

With “The Crystal Ship” on the sound system, Angela led Frankie toward the door, saying stoned good-byes. But Frankie broke off, pushing his wife’s hand away. He stumbled over to where I sat. Leaning down over me, hand on the back of the sofa, he treated me to a blast of beer breath and stale smoke. He did not look good.

“Don’t you let Angela get to you, all right? Don’t let her get to you, when she does that flirting thing of hers. She don’t mean nothing. The bitch just wants to make me jealous. I just wanted you to know that.”

I shrugged. “We were just talking.”

“She loves to talk. Don’t she just? She did her first line of meth last week. Kept me awake all night with her yakking. Listen…” His face was soaked, and he smelled like a high school chemistry lab. “I just wanted to tell you … you’re okay, you know that? You’re okay, man. That song, the new one?” He shook his head. “You’re a mean motherfucker, you know that? But it’s good, you know? I just wanted to tell you … I really … like that song…” He smiled. Smiling wasn’t Frankie’s strong suit. He always tried to hide his teeth onstage. North-of-the-mountain dental care. “I just wanted you to know, all right?”

“Thanks. You’d better go, man.”

“Don’t worry about her. She just wants to drive to where we can pull over and screw. She likes things crazy.”

I thought it more likely that they’d pull over for Frankie to puke. I’d never seen him so far gone. He generally kept his shit together. Tooker had been the one with the problem.

“You need a ride home, man?” Frankie asked.

“I thought you and Angela had plans?”

He closed his eyes and nodded. About to fall as

leep and drop on top of me.

“Yeah … I forgot.”

He woke himself up and showed me his crooked teeth again.

“Just another slut…,” he sang in my face, “who showed up at the ball…”

He staggered back to where his wife stood waiting.

* * *

The beer filtered through and I went out back to water the trees. I didn’t intend to use the outhouse, which was vile.

Approaching the end of the yard, I heard someone behind me. It was Joyce’s biker. And his pal. One in denim colors, the other in leathers. Goatees on hatchet faces in the moonlight.

“You little fuck,” Joyce’s friend said. “I hear you don’t treat ladies with respect.”

I held up my hand in a let’s-talk gesture. The biker knocked it down and stepped in close. He jabbed me in the gut. I closed up like a scissors. Before I could recover, his friend said, “Mark him up good. The cunt.”

I heard bone crack and the biker in front of me dropped hard to the ground. I saw Matty. He landed a haymaker in the middle of the other one’s face, and I recognized the crunch of a broken nose. Mine had been broken in a bar fight the year before and the sound was unforgettable.

Both of the bikers lay on the ground, the first crumpled and motionless on his side, the other on his back like an overturned insect, covering his face with both hands and moaning. Seeping between his fingers, blood shone in the silver light. There had been no real fight.

“You okay?” Matty asked me.

“Yeah…,” I gasped. Still chasing breath. “Yeah … Shit.”

“Want to head home?”

Matty didn’t even look back to see if the bikers were coming after us. I thanked him, but he didn’t respond.

When we got to his car, he said, “It all happens very fast. It’s always very fast. If you’re not fast, you’re dead.” I wasn’t certain he was talking to me. Then he said, “Wait here.”

“Where’re you going?”

“Joyce.”

He returned without her.

We drove toward Pottsville on the Tumbling Run road. The headlights drilled a tunnel through the forest.

Just short of the reservoir, Matty asked, “Did you think of anything?”

“Anything what?”

“A new name for the band. You were just sitting there all night. I thought maybe you were thinking about a name.”

He seemed hopelessly naïve, believing that I could cook up a new name so quickly. On the other hand, he was right.

“How about the Killerz? With a ‘z’ on the end, the same as with the Destroyerz. We’d be saying that we’re a different band, but there’s continuity, too. For the people who are already fans.”

“That’s no good.”

“Then how about something ironic?” I’d been setting him up for the name I truly wanted.

“What’s the name?”

“The Innocents.”

We stopped at the intersection with Route 61 and turned right.

“You think that’s a good name?” he asked as we passed the car wash.

“Yeah. The critics would get the point.”

“I’ll talk to Frankie and Stosh. You don’t mind me saying it’s my idea?”

“No, man. Do what works.”

“Want to go by the Coney for a dog?”

I was tired and not really hungry. But I said, “Sure.”

In Pottsville, the stores that hadn’t gone broke slept: Pomeroy’s and Green’s, the Sun-Ray and the Grace Shop. There wasn’t a derelict left on the sidewalks.

“Those bikers were from the Warlocks,” I said. “They’re a Philly gang. Doesn’t that worry you?”

Matty pondered the question for the length of a red light. “They’re punks. Or they wouldn’t have come after you together. They’ll be too embarrassed to say what happened.”

We parked by the Capitol Theatre and crossed the street to the all-night Coney Island. I figured we’d eat and leave, but Matty ordered a second chili dog and another glass of chocolate milk, then coffee. And he talked. In that slow, squeeze-out-the-words way of his, as if unwilling for the night to end. The knuckles of his right hand were bloody, but he said his fingers were fine.

“I’m going to work with Stosh for the summer,” he said at one point. “Up his old man’s bootleg hole. It’s good money. When the band gets going right, I’m going to take accounting courses at the McCann School. On the GI Bill.”

I almost said something about the math scholarship but caught myself. I wasn’t sure how Matty would feel about me knowing.

“Everything’s going to be all right,” he said. “As long as I can play music.” Shy, he looked away from me and toward the withering pies in the glass case. “Everything’s going to be all right now. I just want to play music, that’s all.”

“Me, too.” It was the truth. I loved music more than words could express. Only music could communicate what I felt, and one day it would. I was determined that it would. I’d practice, I’d learn, I’d improve. The hour would come when I would play the way I longed to play: as well as Matty did. Better. I dreamed of being famous, fantasizing about women and interviews. But that wasn’t the heart of it. I loved music so nakedly that I could not have told anyone, even if the right words existed. One day, if I didn’t give up, music would love me back. I was willing to sacrifice everything for that.

We talked about the groups we liked and about guitarists. We agreed that our band could be really good, that the ingredients were all there. We just had to want it badly enough, to work hard and not give up. Matty asked me how I’d learned to write songs, and I told him that they just came to me, that I couldn’t explain it. I asked how he knew what to play without even thinking about it, and his answer was identical to mine. The night waitress finally stopped glaring at us and just looked out the window, waiting for a miracle.

THREE

I don’t know which one of them started it, but by the second set Frankie and the go-go girl were flirting in front of the crowd. Half of the audience probably thought it was part of the act, while most of the rest didn’t care. But things became flagrant even by Frankie’s standards, and I worried about word getting back to Angela. We always covered for Frankie, but there were limits.

The stage at the Greek’s was cramped, with an outlying platform on each side of the dance floor. The stands were for the go-go girls, who were a serious draw for the locals but a pain in the ass for us. The girls weren’t strippers, but they were barely a half-step up, performing in skimpy bikinis and, sometimes, go-go boots. These weren’t the scrubbed kids from the teen TV shows, but hard numbers out of Philly or Reading. They worked a circuit around eastern Pennsylvania, dancing two weeks in one club and then moving on. They were often bruised in unexpected places.

The music had to support the girls’ routines, and we had a list of songs that usually worked, such as “Let’s Spend the Night Together,” “Sock It to Me, Baby,” and a bubble-gum-meets-Playboy number from the Blues Magoos, “Take My Love and Shove It Up Your Heart.” On weekends, with couples in the audience, we played two slow numbers per set, but only one, on the funky side, when the girls were the main attraction during the week.

The Greek’s was the roughest club we played, in the toughest town in the coal region, Shamokin. The joint’s real name—in neon—was “The Athena,” but everybody in the business just called it the Greek’s. Spiro, the owner, was known for his Mob connections, evidenced by his bouncers’ freedom to beat drunks to a pulp without fear of the law. When you played Shamokin, you never knew if the night would end in a brawl or a mattress party.

That night was the last gig we played under contract as the Destroyerz. We planned to take a month off to polish new material and to work on more originals. Then, in September, we’d come back as the Innocents. Stosh and Frankie were already booking jobs, with Frankie the face of the corporation and Stosh as the accountant. I never knew a drummer who didn’t handle the money.

So we all

felt upbeat and loose, although there was an income gap ahead. We believed in the band and argued surprisingly little. But that night at the Greek’s, Frankie was feeling too loose.

We played “Light My Fire,” which had been off the charts for a year but remained the most requested song in the region. Matty did a stunning take on the organ part, punching on his fuzz tone and working his wah-wah pedal to make a sonic miracle. It didn’t sound exactly like an organ—there was no way to get that fullness on a guitar—but Matty came eerily close.

Of the two dancers that night, one was overweight and cranky, with bleached hair, black roots, and a belly scar that looked like a centipede. When she danced, you just wanted to look the other way.

The second woman was another story. Compact and lean, with a helmet of black hair and a carnivore’s eyes, she looked vicious, depraved, and alluring. Skipping the slut moves most girls repeated, she made dancing erotic through black magic. The eternal vixen, the siren from someplace dark, her name was Darlene, and she scared me.

Frankie was up for it, though. He stole moves from every singer who impressed him. At first the lifts were obvious, but over the weeks he somehow made them his own, becoming greater than the sum of the countless parts he pilfered. On a good night, he ruled the crowd. But Darlene conjured a buried side of him from back in the Famous Flames days, when the boys played stag parties at the Elks or the Odd Fellows. One of their popular numbers had been “I Love You So Much I Could Shit.” The other tunes were less edifying. Now Frankie thrust out his crotch as Darlene waved her butt at him, licking her lips at the men around the front tables. When he sang, “Come on, baby, light my fire,” it was all a bad act from a strip joint.

As we finished the song, Frankie stepped over to me.

“Hey, I’m going to sing ‘Shake Your Moneymaker’ tonight. All right?”

That was one of the few songs I got to sing. Except for the simplest harmony parts, I was restricted to one or two of my own songs and the occasional up-tempo blues number, “Look Over Yonders Wall,” or “Got My Mojo Working.” Frankie, Stosh, and Matty had all been choirboys. They could blend their voices on anything from the Byrds to Philly soul. I didn’t fit.

The Hour of the Innocents

The Hour of the Innocents