- Home

- Robert Paston

The Hour of the Innocents Page 30

The Hour of the Innocents Read online

Page 30

“Elmira, New York.”

“That’s a long way from here. Isn’t it? You’re a long way from home. In fact, that’s all the way across a state line. How old are you, miss?”

“Fifteen.”

“And who brought you all the way down here from Elmira, New York?”

She hesitated, but only for a moment. Then she pointed to Matty. “Him. That guy. He did it during the night. He said it was so nobody would know.”

“Why don’t you get back in the car now, honey? You’re getting soaked. We wouldn’t want you getting sick.”

Uncle John turned to Matty. His smile could not have been grander. “So … we have a large quantity of what are obviously illegal narcotic substances. And large bills—I wonder if they’re marked? Plus a fifteen-year-old girl carried across state lines for immoral purposes. I bet she’s going to swear you gave her drugs, too.” He inched closer. “Do you have any idea how many years they’re going to put you away for? Do you have any idea how long you’re going to be locked up, you worthless punk?”

Uncle John sneezed. And Matty broke his neck.

It happened in a blur. Faster than a raindrop could dissolve. The big cop didn’t have time to squeeze off a single round. Roaring like a maddened bull—or a Minotaur—Matty reached out and snapped his uncle’s neck. It sounded like ice cracking.

Sergeant John Tomczik fell onto his back, eyes open to the rain. When he grasped what had just gone down in front of him, the young cop fired.

He shot Matty three times. Matty never moved toward him or made any effort to evade what was coming his way. He stood there, hands at his sides, as the cop shot him in the chest and in the arm, then, as Matty fell, at the base of the neck.

Matty’s outstretched arm crossed his uncle’s ankle.

The girl screamed from the inside of the car. Shattered glass had cut her.

The rookie officer pointed his weapon at me.

“Don’t shoot!” I said. “Please.” Slowly, I raised my hands from the hood. “I’m unarmed. Don’t shoot.”

The window of danger passed. The cop looked away from me. To stare at what he had done. The hand holding his gun dropped to his side. His expression lost its courage, then its coherence.

“Can I check on him? To see if he’s still alive? Please?”

“Oh, my God,” the cop said.

The girl in the backseat kept shrieking.

I walked around the car, slowly, keeping my hands in the air and my eyes on the cop. He didn’t raise his gun again. He barely moved.

I knelt beside Matty. It was all so undramatic, so nothing. There were no last words, no messages to Angela or his mother. He was dead in the right lane of the Frackville grade, with the rain already washing his blood away.

“Oh, my God,” the young cop repeated.

TWENTY-FIVE

The morning of the funeral, my mother’s lawyer showed up at my door before business hours.

He didn’t bother with greetings, just said, “May I come in? We need to have a conversation that isn’t suitable for the office.”

I let him in. He looked around. As if amazed that the opium den wasn’t littered with naked bodies and crawling with rats. I had never liked him, not even when he was a friend of my father’s. My mother’s manners had ruined me, though, and I offered him a cup of coffee.

He declined. “May I sit down?”

“Sure. Sit down.” I sat down, too.

“I want you to understand that our conversation is strictly confidential. I don’t intend to mention most of this to your mother, or to anyone else. Just so you understand.”

“All right.”

Not an especially handsome man, he had something about him—perhaps his success—that had made him attractive to women. He had a reputation at the country club.

He cleared his throat.

“Will, the police are willing to forgo any charges against you. There won’t be any record of your presence at the scene of the incident.”

“What charges? Jesus Christ. A state cop set up an innocent man. Then another cop shot an unarmed man. What kind of goddamned bullshit—”

“Calm down. We need to discuss this as two adults.”

“Mr. Levenger … my friend’s dead. Dead. He was murdered. For all intents and purposes.”

“That’s not how the authorities see it.”

“Which authorities? Which ones exactly? The cover-up-our-asses state police? Anybody else?”

“Will, I don’t think you understand the potential gravity of the charges that could be lodged against you.”

“Like what?”

“Abetting trafficking in narcotics. Abetting the corruption of a minor. Accomplice to murder. And the murder of a law enforcement officer, at that.”

“That’s bullshit.” I was up on my feet. Ready to smash things. Or break into tears. “That’s complete bullshit. And everybody knows it. Let them charge me. Just let them. Let them put me on a witness stand.”

He waited me out, then asked, “Are you finished? Can we discuss this now?”

I dropped into my chair. My eyes had grown wet. I fought it.

“Will, what’s done is done. Complicating your own life isn’t going to bring your friend back. Serious errors were made, I grant you that.” He looked around furtively, a worried member of the underground in an old war movie. “In fact, there’s been an appalling miscarriage of justice. That hasn’t gone unrecognized.”

“Don’t you believe in justice? Don’t any of you?”

“That’s why I’m here, Will. Because I want to see justice done. To the extent still feasible. And partly because of my respect for your mother, of course. I don’t want to see an injustice done to you.”

“I’d win in a court of law.”

“Will, you don’t know that. This isn’t Perry Mason.”

“What is it, then?”

He looked around again. As though the Gestapo might peer in through a window.

“It’s Schuylkill County, Will. Forget it.”

“It isn’t right.”

“No. It isn’t. I grant you that. But you couldn’t win. No matter what happened. You can’t win. Let it go.”

I put on my most cynical face. But I hadn’t lived long enough to make it convincing.

“Are they willing to give me back my driver’s license?”

“No.”

I looked past him at the gleaming day beyond an unwashed window. Levenger was good at his job. He knew when to wait. And he waited.

When I was sick enough of myself, I wiped my face and said, “This sucks.”

“Yes,” he said. “It sucks. I take it that means you agree to the proposition I just explained?”

I nodded. He got up to leave.

With his hand on the doorknob, he brightened. “I almost forgot. We have some good news. There’s a buyer for your mother’s house.”

* * *

I suppose you don’t care what the weather is like on the day they bury your ass. But I was glad of the sunlight and warmth, of the green glory days of rain had coaxed out of the landscape. The radiance of the world beyond the Catholic cemetery seemed like a belated gesture of decency toward Matty. On behalf of whatever power screws with our lives.

About fifty people showed up. Family. High school friends. Fellow musicians who stayed to the rear of the crowd. Joey and Pete. Stosh and Red. Me.

Angela wasn’t there.

And Frankie didn’t show, of course. His parting gift to me had been to start a rumor that I was the one who set up Matty. I don’t think many people, if any, believed it. But they hedged their bets and kept their distance.

Matty’s old man refused to have an honor guard from the American Legion. He showed up drunk and crying. Matty’s mother proved surprisingly tough.

There wasn’t much to say, beyond the official words. I recall the plastic flowers on nearby graves and the breeze flirting with the priest’s cassock. I walked a few yards behind Red and Stosh as we headed

back to our cars. They supported each other, arm in arm.

* * *

Angela had disappeared forever. There was an early rumor that she was living with a spade who dealt heroin down in Reading, that he was working her. But I knew what rumors were worth. After that, she was gone from the face of the earth.

As the years went by, I passed through Pottsville now and then. I heard that Frankie was dealing blackjack in Las Vegas. On my next visit, a decade later, I learned that he had come home to take over the printing business after his father died. He had married his youngest sister’s best friend and they had a couple of kids.

Stosh and Red escaped for good. I ran into Stosh in 1997. Caught in the usual flight delays at O’Hare, we recognized each other immediately. He had made a decent life for himself as a session drummer in L.A. before getting into real estate. He was headed to France on vacation with his partner, Brian, a dainty young version of Matty. Brian was a digital animation artist at Disney. Stosh was enormously proud of him. The three of us had a couple of rounds in the bar.

Stosh told me that Red was doing great, after recovering from breast cancer. She was the director of a women’s arts project in Santa Barbara. He suggested I look her up the next time I was out on the coast. He told me she still talked about an old girlfriend of mine.

I never learned what became of Laura Saunders, but my mother lived happily ever after. In Connecticut.

* * *

But that’s getting ahead of the story.

With my stereo packed up, I was listening to pop junk on a transistor radio as I loaded my last possessions into boxes. My Pottsville life was about to go into storage, joining a few crates of my father’s things. The June weather was unusually hot, and the window fan merely pushed the air around. Sweat had glued my tank top to my skin. I was tired.

Male footsteps climbed the outside stairs. My final visitor, whoever that might be.

It was Joey.

“Hey, man,” he called through the screen door, “I thought you were already gone.”

“Then why’d you come?”

“I thought maybe you weren’t gone yet.”

“Come on in. And don’t worry. You missed the serious work.”

The door clattered shut behind him. “When was Joey Schaeffer scared of work? Feel like smoking a little weed? For old times’ sake?”

“No.”

“Me, neither. I don’t know what’s the matter with me.”

“Tell Pete I’m sorry I’ll miss his wedding.”

Joey sighed and dropped into one of my landlady’s chairs. “I give her three hundred and sixty-five days before she weighs three hundred and sixty-five pounds. Pete’s gaining weight himself, all in the gut.”

“Pennsylvania Dutch cooking.”

“Yeah. Shoofly pie. I never could stand it.” He considered the stacked boxes, the separate odds and ends. “Want to sell your guitar?”

“I’ll sell you the Rickenbacker. Two hundred.”

“I meant the Les Paul.”

“Not for sale.”

“You taking it with you?”

“No. But it has sentimental value. If you want something to drink, there’s beer in the fridge. And some orange Kool-Aid.”

He got up again. “Christ, I am getting old. I think I’m going to go for the Kool-Aid.”

“It’s the heat. Fill mine back up, too.”

We paused amid the ruins and drank our sugar water. “You ought to stick around,” he told me. “Just for the summer. I got tickets for the thing at Woodstock. I’d rather go with you than with some chick. There’ll be plenty of hippie ass to go around. They’re expecting, like, ten thousand people.”

“Already bought my plane ticket.”

“Quo vadis, brother?”

I considered him. “Joey, why do you always have to play dumb with everybody but me? And with me, half the time?”

“Because it works.”

“As far as ‘wither,’ I’ll know when I get the passport stamp.”

“The hero on his quest. Send me a postcard, okay?”

“I will.” I sat on a box. “You know, you’re the only person left I’m going to miss.”

He grunted. “You won’t miss me much.”

“I didn’t say ‘much.’ Just that I’d miss you. So what’s next for Joseph P. Schaeffer?”

He let me see one of his intelligent smiles, the kind reserved for a very few initiates. “Funny you should put it that way, Mr. Cross. I’m selling the sound system. And the van. Got a couple of bands interested. Some kids from Schuylkill Haven want me to do sound for them, but they just don’t have it. I’ve been spoiled. So I’m quitting while I’m ahead.” He finished his Kool-Aid and made a face. “My dirty, filthy secret is that I’m thinking about going back to college. I’ve dicked around enough, I ought to get serious. I mean, how many parties can you throw before it stops being fun? I figure I’d rather stop while it’s still fun. Except, to tell you the truth, it isn’t fun now.”

“It used to be the Party of the Century. Once a week.”

“Yeah, well, my brother’s getting out of prison. I thought I’d set a good example.” He grinned. “You know where I’m coming from, man. I told you before: We’re survivors, you and me. Like in that song of yours.”

His grin evolved into mild and merry laughter. “Come back in twenty years, and you’ll probably find Mr. Joseph P. Schaeffer behind a big desk down at the bank, just like my old man. With a potbelly and a three-piece suit.”

“Why don’t I have the least trouble imagining that?”

He grew pensive. “Sometimes I wish I hadn’t been such an asshole while my parents were still alive. I mean, I was really the shits to them.”

“Welcome to the club.”

He smiled again. But it wasn’t the same. “My father used to say regrets are for losers. Sentiment wasn’t his bag.”

“I guess you can take that to the bank.”

He chuckled. “That’s good. You always were a sharper customer than you let on yourself.” Our eyes met. “You and me, two born cons. Everybody else thought it was for real, the poor bastards.”

“It wasn’t that cut-and-dried.”

He lifted one shoulder in an economical shrug. “Maybe not.” A siren sounded, then died away. “Guess I’d better get a move on. Before you put me to work. Vaya con Dios, brother.” He stood and stretched. The fan buzzed. “It’s been a hell of a year, though. When you think about it. We came so damned close. Before Frankie ruined it all.”

“I don’t want to talk about Frankie. Anyway, it’s amazing we got as far as we did. As screwed up as it all was.”

“It was incredible, though. For a while. You got to admit it. I mean, the music was really something. I was there, man, I heard it. It was magic. And what a crazy-ass bunch of people, you couldn’t make them up.”

“Don’t romanticize it.”

“Come off it, man. You had a blast.” One of his Mad Joey ideas struck him, I could read it on his face. “You’re good with words,” he said. “You ought to write a book about the band and all.”

I grimaced. “I just want to forget everything that happened and every one of those crazy sonsofbitches.”

He laughed and said, “You won’t.”

AUTHOR’S NOTE

As she finished reading the manuscript of this novel, my wife asked, “Which sixties band did they sound like? Did you have a specific group in mind?”

The straightforward answer was that I heard the band as itself: The Innocents were the Innocents, playing songs I’d written many years before.

Yet as soon as I finished answering her, I realized that there was one band and album that did come very close to the sound of my imagined group. The first, brilliant, furious Moby Grape album, simply titled Moby Grape, is worth tracking down both for its still breathtaking quality—the wild, unleashed joy of a too-brief era in music—and as a good soundtrack for the tale of the Innocents and the women who enraptured them. Listen to “O

maha” or “Hey Grandma,” to “Changes” or “Fall on You,” inserting a few Jimi Hendrix guitar solos to give Matty his due, and you’ll have the sound this novel sought to conjure.

Grotesquely mishandled by their record company, the members of Moby Grape never broke through to find the success they deserved. Nor did follow-up albums, with changing band rosters, regain the wonder of that first recording. Moby Grape was all about the original cast; together, its members were greater than they managed to be on their own or in other combinations (although each did fine, often fascinating work). Musically, they belonged together. Yet they could not endure as a human community. Perhaps that, too, sounds familiar.

—Robert Paston

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

After splitting from his band, ROBERT PASTON embarked on an adventurous, wide-ranging life. He now lives under tall trees with his wife and a few good guitars.

This is a work of fiction. All of the characters, organizations, and events portrayed in this novel are either products of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously.

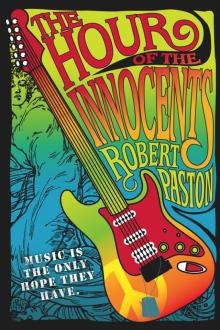

THE HOUR OF THE INNOCENTS

Copyright © 2014 by Robert Paston

All rights reserved.

Guitar illustration by David Turton/Getty Images

Cover design by Jamie S. Warren

A Forge Book

Published by Tom Doherty Associates, LLC

175 Fifth Avenue

New York, NY 10010

www.tor-forge.com

Forge® is a registered trademark of Tom Doherty Associates, LLC.

The Library of Congress has cataloged the print edition as follows:

Paston, Robert.

The Hour of the Innocents / Robert Paston. —First Edition.

p. cm.

“A Tom Doherty Associates Book.’’

ISBN 978-0-7653-2681-2 (hardcover)

ISBN 978-1-4668-1540-7 (e-book)

1. Rock groups—Fiction. 2. Nineteen sixties—Fiction. I. Title.

The Hour of the Innocents

The Hour of the Innocents