- Home

- Robert Paston

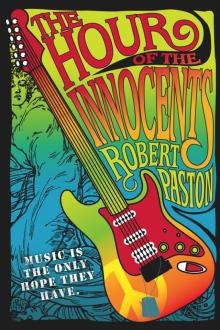

The Hour of the Innocents Page 7

The Hour of the Innocents Read online

Page 7

“They gave the crazy fucker a Silver Star.”

“Matty won a Silver Star?” I’d read enough Sergeant Rock comics and seen enough episodes of Combat! to know that a Silver Star mattered.

Gerald laughed. Tee-hee. “He didn’t tell you that, man? John fucking Wayne didn’t tell his homeboys?”

“No bullshit, okay? Matty really has a Silver Star?”

Footsteps approached.

“Shit, no. He got two.”

* * *

Mrs. Carley had to stretch to feed us, and the food wasn’t southern cooking as described by Eudora Welty, but I was grateful enough to take it seriously when she thanked the Lord on our behalf. Eating was rarely at the top of Matty’s priorities, although he became impulsively hungry at odd hours. The fried pork cutlets, lima beans, and mashed potatoes put something in my gut for the march ahead.

A laden twist of flypaper dangled above a loaf of bread. The iced tea was sweeter than Kool-Aid.

Our hostess gave Matty an enveloping hug when we left, nodding in my direction. With Gerald toting his saxophone case and teasing Matty about his choice of automobiles, we headed off to a Sunday afternoon jam session. Gerald was anxious to show off Matty’s playing, remarking that “these cats never heard a white boy play.”

The venue was a blinds-down club where the cigarette butts from Saturday night still lay on the floor and stray glasses remained on tables. The music was as confused as the times. Old dudes with conk-job hair and shiny suits blew cool jazz, while younger musicians with beach-ball Afros and sunglasses pushed the jam toward electric funk. Blues wasn’t on the menu. We sat and listened. Sitting through a full rotation of musicians seemed to be the dues you paid before approaching the stage with your ax.

Instead of reacting against the appearance of two white guys, the musicians and their all-male audience ignored us. It was our turn to be invisible.

Gerald stepped up to take his turn as an ancient drummer who worked with brushes gave way to a sticks man in an African smock. Gerald spoke to the new drummer, then to the dude playing the house piano. The jam moved into a phase that wanted to be electrified Coltrane but drifted between bursts of notes and awkward gaps. Meant to be impudent, the beat meandered. Given Matty’s interest, I expected Gerald to be an impressive player, but every time he started to get going, he fell back on stock riffs. His breath control seemed off, too. The bass player was good—an old-fashioned walking man—but the drummer just wanted to break things.

As that round of music petered out, the old guy who’d been doing a Wes Montgomery imitation on the guitar unplugged and stepped offstage. Gerald motioned for Matty to come up. As he crossed the unswept dance floor with his Stratocaster, the audience of musicians moaned theatrically. One loud comment warned of “faggot noise.”

Then Matty played. The small crowd’s initial reaction was to lean forward and check their ears. The keyboard man began calling changes in key and rhythm, determined to stump Matty. But Matty followed every shift easily. When the trumpet player stepped over to challenge him with a call-and-response, Matty played back every Dizzy Gillespie swoop and curl perfectly. He did the same with Gerald and his sax, then with the piano man. By that time, the other musicians in the room were hooting encouragement, marveling at the talking dog, the white guy who had real chops.

The problems began when Matty took the lead. He dispensed ear-teasing lines and what-was-that? jazz chords so swiftly that I didn’t recognize the musician who played with the Innocents. The chromatics were more complex than anything I’d ever heard him play. Nobody could repeat his riffs back to him. And the irony was that Matty never meant to show off. I understood that in my bones. When he played music, he just became oblivious. The demons in his fingers took control.

The jam session tradition calls for musicians to try to cut one another, to outshine rival players. But Matty wasn’t out to cut anybody. He was just letting the music inside him escape. And he didn’t know how to stop. He wasn’t greedy. He scrupulously let the others take their turns at soloing. But each time his turn came back around, he humiliated the other players. He might as well have burned a cross on the corner.

Everybody in the room sensed the swelling tension. Everybody except Matty, who played with his eyes closed, having the time of his life.

The other musicians let the jam die. Gerald quickly took Matty by the arm. Time to go.

As he packed up his Strat, Matty finally came down from the clouds and sensed that something was off. He wanted to say good-bye to the cats. But nobody was interested. He didn’t get a word out of them.

One player spoke to Gerald as we left, though.

“Junkie.”

Out in the street, Matty turned with a question, but Gerald, who looked shattered, addressed me:

“You know how crazy this motherfucker is? You want to hear it? He goes to Bangkok on midtour R and R. You know, Pussy-town? Bang-Cock? Where every normal motherfucker rents him a girl for the week. And you know what this fool does? The great Sergeant T? Think he wants any slope pussy? Not him, man. Not Sergeant fucking T. He pays this singsong gook band to let him sit in on guitar for the week. Crazy motherfucker thought all the GIs were clapping and cheering for him when he’s up there. They were laughing at him, man. ’Cause he’s going to go back to Nam and get the shit blown out of him just like everybody else and he don’t want no pussy. Just wants to borrow some cheap-ass Jap guitar won’t even stay in tune. Man, that gook band hated him. Even the whores hated him. ‘You number ten, GI.’ Everybody laughed at him.”

“Come on, Doc,” Matty said. He tried to edge Gerald aside. Gently. “Let’s talk, okay?”

“No more orders for me, Sarge. You crazy motherfucker. What’re you going to tell me? ‘Stop using and go to Sunday school for your free watermelon’? You crazy white motherfucker? Look what you left me with. Look at me, asshole. You should’ve let me die.”

Matty reached to restore his grip on his comrade’s arm. Gerald pulled away fiercely. “This isn’t Nam, honkie. I don’t need you. And you don’t need me. What do you want, my other leg?”

“I don’t want anything.”

“You’re a lying motherfucker. You want everything, man.”

“Don’t be like this, Doc.”

“How should I be? ‘Yes, Sergeant, no, Sergeant’? It’s over, man. Go away.”

“I’m sorry, Doc.”

“Just fuck off, all right? You don’t belong here. You don’t need to come around here again. I’ll send you your money back. I’ll mail it to Asshole, USA.”

He pegged off, lugging his saxophone case. Matty took one step after him, then stopped. We stood. Matty didn’t know what to do, and I didn’t know what to say.

After we’d been standing on the sidewalk for a few minutes, a black cat asked if we were looking to score.

* * *

We were already on the turnpike when Matty spoke.

“You should’ve heard him before. We’d come in from a month in the boonies and just play. But drugs got into him. Being a medic … it’s a lot to take.”

“What happened to his leg?”

“He tried to pull in this cracker kid. From Alabama. No. Mississippi. Corinth, Mississippi. That was it. New guy, cherry. We were spread out, working toward a ville. Kid took a nail. They used to shoot to wound a guy out in the open, usually in the leg, so the medic would come out to get him. They loved to kill medics, they knew it got to us. So they dropped this new kid in a minefield. Private First Class Darryl F. Williams, from Corinth, Mississippi. Skinny kid. I’d just in-briefed him a couple of days before. Doc went out to get him and put his foot wrong. Doc was a short-timer, almost eleven months in-country. Lot of attitude. Officers hated him. But he was a good medic to the end. I saw him carry in guys twice his size.”

Matty clicked on his turn signal. “We put out all the firepower we could and I got Doc back. He was crazy, screaming. Didn’t want to leave his leg behind. Wanted me to find his leg. He needed a tourniquet f

ast. I was sure he was going to go into shock or bleed out. But he didn’t. King Kong and Nick got him back to the company LZ and onto a medevac. But I couldn’t let anybody else go out after the new kid. It was a decision I had to make, they left it to me. He was too far out there, no cover. We just waited while he bled to death. The gooks started yelling at us, telling us to come get him. In this gook English you never stop hearing in your head. They were laughing.”

“He said you have two Silver Stars.”

“That’s not true.”

“What is true?”

He turned on the headlights and drove into the dusk. “You can’t say anything about this. One word, and I’m out of the band. And gone.”

“All right.”

“They gave me one Silver Star. And a Bronze Star before that. They wanted me to stay in the Army, to go to Officer Candidate School.”

“Why didn’t you?”

“I hated the Army. I just wanted to come home. And play music.”

“What did you do? For the medals?”

“It doesn’t matter.”

“There was nothing in the papers.”

“I cut a deal. With an NCO in Public Affairs. At brigade. He wanted a souvenir AK. He yanked the hometown press releases.”

“Why didn’t you want people to know?”

Matty thought about it, gathering words. “No man should be proud of what I did.”

“He said you loved it.”

“Doc never understood.”

“He said you were good at it.”

“That’s different. That was an accident. Like having a good voice.”

“Why did you do it, then?”

A shadow in the dying light, he shrugged. “You don’t get a choice. It’s not like in a book. I wanted to come home. And we couldn’t both come home. Somebody had to die. The other guy, or me. I didn’t want it to be me. It’s nothing to be proud of. It’s something to burn in hell for. Let’s talk about something else.”

But Matty was the one who hadn’t finished talking. “I hated every single day I was there,” he added. We slowed toward the tollbooth at Morgantown. “I didn’t just count days, I counted the hours. I used to do the math in my head.”

With the lights of Reading glowing on the horizon, I asked, “Matty? Why did you want me to come along today?”

“So I’d have to come back.”

SIX

Angela stood on the landing, holding the paperback I had given her. It felt brutally early.

I pushed the screen door open.

“No. I just wanted to give you this.” She held out the book.

“You didn’t like it?”

“He only cares about people like you. And your new girl. He makes fun of people like me. People like me and Frankie. Like we’re dirt.”

“O’Hara didn’t like anybody. Not even himself.” I pushed my hair back off my eyebrow.

“You happy?” she asked. “With her?”

“We just met.”

“But she’s your kind. Isn’t she? I hope you’re happy. Somebody ought to be happy.”

“Angela, it’s just not the way you—”

“I’m a real person, you know that? I’m not just Frankie’s wife. Or some hairdresser slut, like people think. I’m a person, all by myself. And I’m not just somebody to fuck.”

“Keep your voice down. Please.”

“You would’ve fucked me. You didn’t care. Then you jumped right in bed with your little princess. I bet she drinks perfume so her shit won’t stink.”

“Stop it.”

She crumbled. Sniffing back the wetness in her nose, she said, “Do you know what it’s like? To always be on the outside looking in? Wondering when life’s going to start? Real life? Do you know what that’s like?”

She looked as though she hadn’t slept. I was tempted to ask her what drug she was on. But that would have rekindled the scene.

“Just come inside. I’m still half-asleep, okay? Let me get a shirt on. I’ll make a pot of coffee.”

“No. We’d both do something stupid.” She began to cry full force. “I’m better than you think I am. I’m better than you know.”

We both heard footsteps on the stairs and looked down.

It was Stosh. In his work clothes.

“I was just giving him back his book. It stinks,” Angela declared.

Stosh came up beside her. He didn’t look the least bit perturbed at finding his best friend’s wife in tears at another man’s apartment door.

Wiping her face with the back of her hand and sniffling, Angela said, “I got to get to work now.”

Stosh watched her go. She threw herself into her car and slammed the door. Grinning, he nodded at the book in my hand.

“That the one somebody at the salon gave her?”

“Stosh…”

He was wonderfully amused. “Got any coffee in this dump of yours?”

“Listen … nothing happened.”

He waved it all away. “Don’t worry about it. Everybody knows Angela got a thing for you. We’re taking bets on when she’s going to beat the living daylights out of that new girl of yours.”

I led him into the apartment. He had coal dirt on his boots.

“Who’s everybody?”

He laughed. “Even Matty’s probably figured it out by now. He’s the one to look out for, by the way. I just mind my own business.”

“What about Frankie?”

“Frankie isn’t worried. He knows Angela. He thinks it’s funny. Keeps Angela’s mind off what he’s up to. He knows she won’t give you any. Even if she wants to. Nice Ukrainian girl like Angela won’t cheat on her husband for the first five years, no matter what. After that, though, it’s ‘Katie, bar the door.’ You going to make coffee, or not? I got work.”

“You going to quit? When the band gets going?” I lit the burner and set the tin pot over the flame.

Stosh snorted. “Think I want to stay down a coal hole all my life? I’m, what, twenty-three? End of every shift, I spend ten minutes blowing black snot in my handkerchief. It’s a decent living, though.”

“Bootleg holes are dangerous. I worry about you.”

“Naw. You don’t worry about me. You worry about the band.”

The first coffee scent was as beautiful as Julie Christie. Matty and I had stayed up late, playing our guitars without amplifiers. He tried to teach me a few of the progressions he played in Philly, but they made no sense, I couldn’t put them in a logical tonal order. I taught guitar a couple of days a week at the local music store and gave a handful of in-home lessons, while studying privately myself with an old jazzman who’d played with the Dorseys and Goodman until the bottle got him. I practiced three hours a day: scales, chorded scales, alternate fingerings. But what Matty played didn’t conform to anything I’d studied.

“Sugar? Milk?”

“Black. Thanks. Listen, this thing with Frankie?”

“I’m not going to have anything to do with Angela.”

“No, the Joey Schaeffer thing. With the sound system. You’re for it, right?”

“Joey’s going to surprise everybody. In a good way. He’s smarter than he lets on. And he has a good ear. He’s just looking for something to do, something hip.”

“I need you to stay solid on this, though. I’ll take care of Matty. But the three of us have to be solid, if Frankie kicks.”

“What’s Frankie’s problem, anyway? He wants to play that dive in the Poconos. He doesn’t want Joey doing sound for us…”

“I still can’t figure out what’s up with the Rocktop gig. But he doesn’t like Joey because he made a pass at Angela. At one of his parties.”

“Joey makes passes at everybody. Female dogs get out of his way. Anyway, you said Frankie didn’t worry about anybody hitting on Angela.”

“I said he doesn’t worry about you.”

“But he worries about Joey?”

“Angela likes her dope. Joey’s got dope.”

I shoo

k my head. “Joey wants to be part of a band a lot more than he wants Angela. Or anybody else. Besides, he goes for the fifteen-gets-you-twenty types.”

“I need you to talk to Joey, okay? When you get him alone somewheres. Read him the riot act. You’re his pal, he’ll take it seriously from you.”

“I’m not exactly Joey’s closest friend.”

“You know what I mean. He needs to know this is serious. No messing with Angela. Because of Frankie. And no selling dope from behind the sound board. Because of Matty. Matty’s death on that shit.”

“I think it has something to do with Vietnam,” I said.

“Yeah, well, whatever it is … make sure Joey has his shit one hundred percent together, okay? Hey, I almost forgot to tell you: Guess where we’re playing just before Halloween?”

“The Fillmore?”

“Lancelot’s Lair. Down south of Allentown. The place you always wanted to play so bad. We’re opening for this New York band that’s got a record deal.”

“Terrific. Great. Want a refill?”

“Naw, I’d be pissing down the shaft, and I hate to do that. Pissing hunched over like that, then working in it.” He rose to leave, moving briskly all of a sudden. “Just talk to Joey, okay?”

“You got it. Hey? Stosh?”

He paused by the door. “Yeah?”

“What’s ‘covering quarters’ all about?”

His grin grew as wide as his lips could stretch. “Who’s been telling you about Matty? Angela?”

* * *

I ate two blueberry Pop-Tarts, ran a half hour of scales, worked on Clapton’s guitar part for “White Room,” then put Music from Big Pink on the stereo while I took a shower. I faced a full day, including two classes, psych and medieval history, at the Penn State branch campus down in Schuylkill Haven, two go-to-the-home guitar lessons, and an evening band rehearsal. And Laura.

I had never been so infatuated, never known anyone like her. I was vain enough not to question my appeal to her but couldn’t fathom what she was doing at the local campus. Or at Penn State, period. It was a prole school, and she wasn’t a prole. I couldn’t believe she hadn’t gotten a full scholarship to Penn. Or to Princeton. Or Yale. But I was glad of it.

The Hour of the Innocents

The Hour of the Innocents