- Home

- Robert Paston

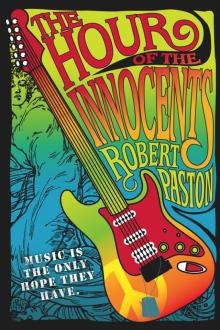

The Hour of the Innocents Page 8

The Hour of the Innocents Read online

Page 8

That Monday was the first day of the semester, when the freshmen sniff one another and the sophomore males sniff the freshman girls. The branch campus held its captives for only two years, then released them to University Park. It was my second year of disinterested attendance. Now and then I considered dropping out, but there was a vestige of pride involved. Although I had been on the outs with my mother for over a year, I lacked the will to disappoint her further. It was bad enough that I hadn’t gone to a serious school. Being a Penn State dropout would have let her write me off forever. Besides, standards were so low at the branch campus that I could miss a week of classes if the band went on the road and still pass.

I parked the Corvair at the end of the lot and crossed to the tiny compound: A single macadam walk connected two buildings that for decades had sheltered the bedridden indigent and aged syphilitics shunned by their families. I expected to see Laura at any moment, yearned to see her.

She wasn’t there. The weather was good, the students were dull, and the instructors were apprehensive. Heavy-legged girls from north of the mountain wore short skirts, kissing the desk chairs with the backs of their thighs and strolling around showing welts. Chalk screeched and earnest young associate profs, thin as saltine crackers, passed out mimeographed pages on which the purple ink had run like blood from Charles Martel and Karl Jaspers. A year earlier, the ROTC kids had harassed me over my hair, which had not been very long. Now my hair fell over my shoulders and they were newly subdued, unsure whether to be proud or embarrassed by the uniforms they were obligated to wear on the first day of class.

Neither Merovingians nor the diagrammed subconscious held my attention. I wanted Laura. But Laura had disappeared.

I was too proud and too cautious to ask any of the sophomore dorm girls I knew if they had seen her. Jewish girls from Northeast Philly—ed. majors every one—or moon-faced Micks from Nanticoke and Scranton, they knew enough about me to warn her off.

Over lunch, I sat in the basement cafeteria and ate a corned-beef sandwich from a vending machine. Still no Laura. A few students asked about the new band. I told them where we were booked in the coming weeks. A number of the freshman girls were noteworthy. But all were minor leaguers compared with Laura.

It occurred to me that I had better read Petrarch.

I checked the library, damning myself for not hitting it earlier. It was Laura’s natural place of refuge. But the only student in the room was a kid with black plastic glasses paging through Popular Mechanics. I would have driven over to the dorm across the highway but didn’t want Laura to think I was chasing her.

Was she avoiding me? I tried to be nonchalant but couldn’t. I felt that I’d tear down massive walls to get at her.

I had to leave to give the two guitar lessons of the day, the first to a woman in Orwigsburg who had decided in middle age that she wanted to be Joan Baez or Judy Collins, the other to a housewife from Cressona who hoped to lead sing-alongs in her church. The latter flirted like a Tennessee Williams vamp and smelled of too much modesty in the shower, but I could charge more for in-home lessons and didn’t have to give the music store a cut.

After two hours of driving, tuning cheap guitars, and the Mel Bay Primer, I returned for a last search of the campus. Except for a few dawdlers—boys with nowhere else to go and plain girls lurking with questions for bachelor instructors—the students were gone for the day. The cafeteria and library were empty.

I gobbled a couple of fifteen-cent burgers at Wixson’s on 61—the cheapest and maybe the worst meal in the county—stopped to grab my guitar, then headed north. I had an hour and a half until our practice session, but I wanted to make a stop.

I drove over the ridge to St. Clair, then up the long grade to Frackville. The Hair Affair salon sat next to a flower shop that lived off funerals.

Angela was finishing up a customer. My appearance surprised her, but she took her time, drawing out the final snips and applications of hair spray. The room smelled of perms and pizza. A plump employee huddled with the receptionist. They snickered at me, and I thought I heard the name “Joyce.”

Thrusting a tip into her bell-bottom jeans, Angela came over at last. She looked worn, fierce, and handsome.

“I just wanted to tell you,” I whispered, “that you don’t have to worry about Stosh.”

Her eyes sparked. “Like I give a shit about Stosh.”

“He didn’t think anything was going on. It’s all right.”

“Nothing was going on. Don’t be so afraid all the time.”

So much for chivalric gestures, I thought. I shrugged and turned to leave.

“Come on,” she said. “Sit down. Let me trim off some of those split ends.”

She levered the chair down to the right height, draped a cloth around me—pulling the neck too tight—then adjusted the angle of my head with her fingertips. Her touch shot white-light voltage.

“What are you so wired up about?” she asked. “You weren’t really worried about Stosh running to Frankie, were you?”

“No.”

She began to caress my temples. “Close your eyes. Girls would kill to have your hair, you know that?”

The scalp massage was disarming. I didn’t want it to stop. For the first time all day, I just let myself be in the moment.

Angela snipped at flyaway hairs. Her comb found an abundance of tiny knots.

“You can’t just brush your hair,” she said. “You got to comb it, too. I told you that last time. Want me to make it just a little shorter? Shape it a little more?”

“No. Thanks.”

“All right. I just need to get this little bit.…”

She cut the flesh under my ear with her scissors. My yelp had barely faded when I found my hand wet and crimson. I was bleeding like a deer hung up to drain.

“Josette,” Angela called with no special excitement in her voice, “get the first-aid kit. And the peroxide.” Meeting my eyes in the mirror, she sighed like the lead in a high school play and said, “I’m so clumsy sometimes.”

We went through the drill of cleaning the cut, then applying Band-Aids that wouldn’t stick. My shirt looked as though I’d dumped a jar of spaghetti sauce over myself. But the wound began to clot. I’d have to rush home to change before our rehearsal, though.

Angela walked me out.

“No charge today,” she told me.

Out of earshot of the others, I said, “You did that on purpose.”

She smiled at me. Her Angela smile.

“I’d never do anything to hurt you,” she said.

* * *

Joey Schaeffer was waiting for us at the warehouse where we held our practice sessions. Never lacking self-confidence, he had already bought not only the promised sound system, complete with new microphones, but a white Ford van to haul it in. He had also brought along a roadie, a guy who had followed the Destroyerz around and who drifted through Joey’s parties. I had never been able to remember his name, which turned out to be Pete.

“I thought you guys might want to try this out before you made a decision,” Joey said.

There was no powwow, no debate. Frankie was all for letting Joey do our sound, after all. I suspected him of tossing in a chip that had never mattered to him, playing it in return for the rest of us accepting the Poconos gig he’d booked for November—why remained a mystery.

Anyway, we were all friends again, high at the thought of our first gig. We were playing a welcome dance for the college kids up in Bloomsburg on Wednesday. It wasn’t the hippest campus in Pennsylvania, but any campus was better than another coal-town bar. And the colleges were dumb enough to pay well.

It was impossible to get the full effect of the new sound system in the warehouse, but it was obviously far better than our old Fender columns. Once Joey got the feedback under control, you could hear every word of the vocals. Joey had done some homework.

On a break, Frankie presented us with the song lists he’d worked out for the sets on Wednesday. When we

argued for shifting numbers around, he agreed immediately. Each set included three of my originals sandwiched between five to seven covers.

The practice went so well that I forgot about Laura for a while.

We soared. There truly is magic in the world. It astonished me that we had come so far so fast. The Destroyerz had been a top bar band. But I saw now that we hadn’t been nearly as good as my vanity insisted at the time. In less than three months, we’d coalesced into a group that sounded professional. With Matty as the catalyst.

Matty the Killer. I already disbelieved most of what I’d heard on the trip to Philly.

* * *

On my way back to Pottsville, I almost skipped my turn off 61 in order to head for the dorm down in Schuylkill Haven. But I would have gotten there just at the end of visiting hours. And I had my pride. I was determined not to run after Laura and make an ass of myself. If she wasn’t interested, she could piss off. I stopped for gas, got a 5th Avenue bar from the old guy working the register, then drove home aching with thoughts of her.

Laura was sitting at the top of the steps, by my door.

“I was looking for you all day,” she said.

SEVEN

It was Frankie’s night. I had been so enchanted and daunted by Matty’s guitar work, I’d forgotten that most listeners judge a group by its lead singer. The heads dug the guitar aces, but the straights just wanted to hear their songs well sung. And Bloomsburg was a straight school, mustering only a few forlorn girls dressed as hippies and half as many boys with shaggy hair. The rest of the crowd could have been held over from 1963. Change was in the air, but most of the students were unsure about the odor.

Frankie was in his glory, though, veering between his peace-and-love persona and teasing sexual swagger. Plain girls anxious to dream and pretty ones tempted to dare gathered closer to the stage as the night progressed. The new sound system amplified the power of Frankie’s voice, as well as Stosh’s blues howls and the three-part harmonies. We opened with “Jumpin’ Jack Flash,” went right into “Born to Be Wild,” and never looked back. Matty played razor-blade guitar that made Keith Richards sound like Granny at teatime, Stosh sweated through his vengeance-is-mine drum parts, and I layered in the middle. But we were all just props for Frankie. Shirtless under a fringed suede vest, with muscles and a narrow waist above striped hip-hugger jeans, he worked the decisive female half of the audience. Red hair whipping and sweat flying, he laid on new moves stolen from the lead singer of the Other Side, a Minersville group that put on a brilliant stage show. If Angela had not come up that night—leading in a constabulary force of her girlfriends—Frankie would have had his pick of the room.

Laura had come along, too. For me, not for the music. In the short time we’d been together, no album I had put on the turntable could convince her that rock was worth a listen. She replied to the Grateful Dead with a recording of Ravel’s String Quartet in F Major brought from her dorm room.

I played with her in mind, anyway. Yearning to break through to her, to excite her. Hoping she would catch at least a light case of the contagion infecting the crowd.

We really were on that first night out. The last month of playing just for one another and a few drifting visitors had made us hungry for the buzz you can get only from a crowd. And that audience was with us from the start. It was intoxicating.

Some of the impact came from Joey’s new sound system, of course. The dance had been moved to a field house, where the bass and drums boomed, muddying the music with echoes. Fortunately for us, Joey and Pete had driven up early. When we arrived to set up our gear, Joey was ready to test the volume levels and balance to minimize the mush effect at the back of the hall. Still, every other factor just allowed Frankie to become the focal point of the hundreds gathered to dance or meet somebody.

Seated on a half-extended set of bleachers, Laura listened dutifully, as if to a dubious lesson. A guy who looked like a probationer on the sociology faculty hit on her but strolled off disappointed. Angela and her hair-dryer harem hung out by the sound board with Joey and Pete, forever judging the competition. Otherwise, every girl who wasn’t dancing with a partner was Frankie’s property.

He rolled his hips and shoulders, then drew back his red hair with both hands, letting his bass hang off his hips like the world’s longest phallus.

“All right, all right,” he said. “Now … something brand-new … one we wrote ourselves just last week … a heavy heartbreak trip…”

It was always a song that “we” wrote, never one I wrote.

“Hideaway” kicked off with a throbbing bass line in E minor. Matty did a high Robin Trower entry on the guitar, strings moaning. Stosh came in, punching up the jagged, move-move rhythm. I colored in the sonic gaps with second-guitar riffs and chords, strut-stepping across the stage toward Frankie.

He closed his eyes, brushed the mike with his lips, and made a girl-you-make-me-suffer face that rose beyond handsome to sublime. He began to sing in a wailing blue voice of seduction:

Hideaway … Hideaway …

Someday we won’t … have to hide away …

Can’t call you up, I can’t … send you flowers,

We meet in stolen moments … we love in stolen hours …

Can’t stop this train, though we … both been tryin’ …

We love so hard that it’s … next of kin to dyin’

Hideaway …

It was one of those songs simple and rhythmic enough to appeal on the first hearing. Frankie made tragic theater of it. I wouldn’t have been too shocked if a coed had crawled onstage to give him a blow job. Between verses, Matty played a solo of molten glass.

At the end, we received the most applause any iteration of the band had gotten for an original song. And that was from straight kids whose highest aspiration was to return to their high schools as teachers.

I couldn’t wait to play for serious rock fans.

Frankie wiped himself down with a towel, as histrionic as James Brown, slipping into his white-spade mode.

“All right, all right, all right! Grab the one you been looking over, fellas. ’Cause here we go now, here we go with ‘A Change Is Gonna Come.’ Make it happen now … hold her heartbeat close … let her know what you’re feeling.…”

I noted that the prick was looking at Laura.

* * *

It was after one in the morning when we got back to Frankie and Angela’s house in Frackville. A workday loomed, but a party was required. Frankie had stashed a half-dozen bottles of Asti Spumante in the fridge, and a cooler of beer sat on the kitchen floor. Joey supplied a brick of Red Leb the size of a Hershey Bar. There were no limits on dope after the gig was over, and even I took a couple more hits than usual. Laura shunned the little bronze pipe and Joey’s proffered match, though. On the stereo, Steve Winwood’s voice insisted that “heaven is in your mind.”

A number of locals had driven up for the band’s debut and they’d gotten the word about the party. In addition to Angela’s girlfriends with their switchblade eyes, a couple of musicians from another band showed up, dragging in their emotional support, including an infamous strawberry blonde who was rumored, alternately, to be frigid, a dyke, or a secret nymphomaniac. She latched on to Stosh, who generally preferred a dollar in his pocket to a woman in his bed. Like Matty, Stosh still lived at home in his twenties.

“You guys were good … really heavy…,” a guitarist from Schuylkill Haven admitted grudgingly. “You heard the Steam Machine play ‘Chest Fever’ yet? Blew me away.”

“I saw those kids in Hunger playing the Moose. Just god-awful. Doing all this Velvet Underground shit. Bass player looks like he’s twelve. Plays his ass off, though, I’ll give him that.…”

“I hear Life’s getting rid of their horn section.”

“I heard they’re quitting.”

“The Other Side’s putting out a single.”

“They getting paid for it?”

I didn’t want to listen to any more musi

cians’ gossip. Nor did I want to sit in on the acoustic jam upstairs in Frankie’s den, a dungeon of Day-Glo posters, black lights, and lint from outer space. I just wanted to be on a mattress with Laura. But she’d been cornered by Angela. Who, to my astonishment, was making Laura laugh.

Matty dropped onto the sofa beside me, bottle of beer in one paw.

“You okay, man?”

“Yeah. Just tired. Hash knocks me out.”

“It was good. You know that? They liked your songs.”

“Our songs,” I said.

“No. They’re yours. Don’t mind Frankie.”

“The crowd loved him. I don’t think I really got it until tonight. How charismatic he can be, I mean.”

Matty yawned. “I start at the McCann School tomorrow.”

“Accounting. Right?”

Matty nodded. “Think I’ll head home.”

He raised his bottle of Yuengling, then lowered it again without drinking. He didn’t move for the door. We listened to Frankie scatting blues upstairs. The guitarist from Haven was trying to play slide guitar but didn’t understand open tunings.

Laura eased away from Angela, smiling still. But she wore a social smile now, the kind my mother wielded.

She edged in between me and Matty, forcing us to give her little rump space on the sofa. “You both should be very happy,” she said gaily. “Everybody loved you.” She turned to Matty. “I thought you were very good. I could tell that much.”

“That’s a major compliment,” I told him. “Laura’s not impressed by the kind of music we make.”

“That’s not true,” she said. “I never said I wasn’t impressed. I just said I don’t like it.”

“What don’t you like about it?” Matty asked. Reticent around women, he sounded genuinely curious.

I saw Stosh slip out the front door with the strawberry blonde.

“It’s … it’s too disorderly,” Laura told him. “There’s no discipline … no rigor. It’s all just energy, uncontrolled. There’s something anarchic about it. Nihilistic.”

“That’s the point,” I said. “It’s a revival of the Futurist philosophy of creative destruction.”

The Hour of the Innocents

The Hour of the Innocents