- Home

- Robert Paston

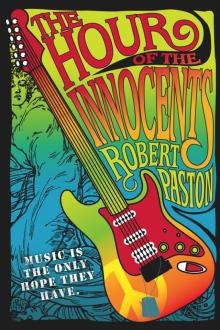

The Hour of the Innocents Page 9

The Hour of the Innocents Read online

Page 9

“The Futurists were fascists. I concede the point, though. There is something fascist about your music. That album you played … the Jefferson Airplane … half the songs sound like marches for masses headed off a cliff.”

“It’s existential.”

“No,” Laura said, “it’s not. It’s self-indulgent. It’s talent in the service of ego, not in the service of art.”

“All art emerges from the ego. Caravaggio … our favorite faggot…”

“You’re stoned. You even smell stoned. Your music may move people, delude them even. But it isn’t art.”

“But it’s fun,” I said.

“That’s dishonest. You believe it’s more than that. You take it seriously. I know you do. You can’t not take things seriously. I knew that about you the moment I saw you. All your laissez-faire posturing is nonsense. You think you’re going to change the world. But you don’t know how hard the world is to change.”

“Do you?”

Laura twisted around to face Matty. Framed against him, she looked like the prim mistress of the manor interrogating a peasant giant.

“What do you think?” Laura asked. “I think you love music, you really do. But do you think it matters in the great scheme of things? I’m not trying to be insulting. I just want to know if you believe your music makes a difference?”

“It makes a difference to me,” Matty said.

* * *

Driving down the Frackville grade toward St. Clair at four A.M., Pete wrecked Joey’s van. Pete was so stoned that he walked away undamaged, immunized from harm by a vaccination of hashish and beer. But the Ford was finished.

The next day, Joey bought a new van. It made me wonder how big his trust fund really was.

* * *

“‘’Tis true, ’tis day; what though it be? O wilt thou therefore rise from me?’”

“Rise and shine, Cleopatra. Places to go and things to do.”

“That wasn’t Shakespeare, it was Donne,” Laura said.

“And it’s after nine. You have classes.”

She drew me back toward her warm white breasts. “‘An age in his embraces passed, would seem a winter’s day…’”

“That’s not an accurate quotation. And it’s not winter. And the citation of poetry is the enemy of sincere emotion.”

“Who said that?”

“I did. I just made it up.”

“Please make love to me again. I want to feel you in me. I love it so much.”

Later, as the hour burned out, she clutched me like a refugee unwilling to give up a last bundle of possessions.

“I wish we could just stay like this. Forever.”

“We’d get bedsores.”

“Don’t be so prosaic. Please. When you can be so romantic.”

I was calculating how I would fit my three hours of practice into the form of the day.

“All right. We’ll stay here forever. But no books. You’ll be bored to death by lunchtime. Let me get us some coffee.”

“Don’t go. Not yet. Five minutes.”

The darkened eyes of sleeplessness only enriched her beauty. I realized there and then that I lacked the poetry within to describe her adequately. Maybe that’s what made me want to rise. The gorgeous collision of our bodies only left me feeling outclassed by something intangible. I drew out the physical until she was pained and raw, but the Laura that mattered most had not been penetrated.

I wondered if she made me feel the way Angela felt about me.

“Coffee,” I said. “Now. Let me up.”

“The brute takes what he wishes and departs.”

In the doorway, I turned to look at her again. I almost said, “I love you.” I ached to say it. But I was afraid she’d laugh and tell me it was far too soon to know. She wanted romance, even possession, but I wasn’t sure how Laura felt about love.

“How many sugars?” I asked.

* * *

The sun was out again and the Schuylkill River ran bright pink, its daily color determined by the dye works. The gorge that funneled the highway remained a heavy, end-of-season green, waiting indifferently for autumn.

“May I see you tonight?”

“I’m unavoidable. But I really do have to study first. And I can’t study while you practice.”

We passed the painted Indian head on the mountainside.

“I’ll pick you up afterward. I’ll be parked down the road. Same place. At ten thirty.”

“Do you love me for myself alone? And not my yellow hair?”

“You don’t have yellow hair.”

Curled against the passenger door, she smiled. “I’ve always been glad of that, actually. It seems so common.”

“Speaking of blondes … you seemed pretty tight with Angela last night. You told me she was a vampire.”

“She is. But maybe she’s not as bloodthirsty as I thought. I don’t know. I don’t want to be a snot. And she really was nice to me, she tried to make me feel welcome. Although she did give me the third degree.”

“About me?”

“Is there no end to male vanity? No. About me. Anyway, I’ve decided I won’t be petty. I think my initial reaction to her was nine parts jealousy, one part insight.”

“Trust the insight.”

“I’m not going to let her intimidate me.”

“That’s different.”

“You really didn’t sleep with her, did you?”

“No.”

“Please don’t.”

“I won’t.”

“Promise me that. Just that one thing.”

“I promise.”

“You’d break my heart,” she said.

* * *

After enduring a stumbling lecture delivered from disarranged notes on the legacy of late Roman political forms among the Franks, I left the campus and the Carolingians, stopped by the Acme for a bag of groceries, dropped them off at my apartment, then drove to the house on Mahantongo Street.

I parked down on Norwegian, out of sight, and walked up the alley to the carriage house. It needed a coat of paint. I let myself in the side door with my key.

I didn’t turn on the light. The unwashed windows let enough sun filter in to define the interior. It smelled of oil and of exhaust fumes absorbed into the wood since the Harding administration. Between the workbench and my father’s car, there was barely room to open the driver’s-side door. I didn’t bother. I just stood there.

It always surprised me, when I came back, to find the car still there. It was a Chrysler Imperial, the last automobile my father bought and a source of friction in the failing household. My mother considered its purchase a faux pas. She called the Chrysler a “Jew car.” Her family had driven Cadillacs since the 1920s, including the second-to-last Caddy to roll off the assembly line—body by Fisher—at the start of World War II and one of the first to roll off when production resumed again in a different world. My father had no money sense, and the Chrysler had been an amateur’s attempt to save a few bucks. He should have tightened his belt at a different notch.

I leaned back against the workbench. At which my father had never worked. He had been educated above the ability to use his hands effectively.

I was not ready to look. I just stood there. A doomed fly looped below the exposed beams.

Why didn’t my mother just sell the car? It was ugly. She hated it. And she needed the money. She still had her big-finned Cadillac, aging but proper.

At last, I turned about. Gripping the lip of the workbench with my eyes shut. Then I forced myself to open them.

I could no longer tell if any bloodstains remained. Mrs. McClatchy had scrubbed them away, even before the police gave their permission. But sometimes I imagined that blood reappeared on the surface of the wood. Like the handprint of the Molly in the jail, whitewashed for ninety years but ineradicable.

No attempt had been made to fill in the gouges where the cops pried out the bullet. The splintered wood still looked naked, pale and shamed, against the dar

ker tone of the studs and the wall.

I hated to cry. I had sworn that no one would ever see me cry.

“You cocksucker!” I shouted. “You worthless, weakling, coward bastard. You coward, coward, coward, coward, coward…” I came to the end of words and howled for a minute.

When I opened my eyes, the light in the bay had changed.

My mother stood in the doorway.

“It doesn’t help,” she said. And she walked away.

EIGHT

We had no interest in Buzzy Ritter’s party. Matty didn’t know him, and I had been on the outs with Buzzy since March, when his attempt to acquire me as one of his acolytes ended in mutual disappointment, acid-trip hangovers, shots from a deer rifle, and a final, repugnant vignette with two girls at his farmhouse. Reputed to have the highest IQ ever recorded in his Dutch-country high school, Buzzy had dropped out of Columbia. After drifting to the West Coast and then Colorado, he came home to be a god or, at least, an avatar. In short order, Buzzy had taught me enough about casual evil to awaken a dormant Puritan streak in my character.

I had shunned him for six months. But the stars in the heavens are tyrants.

Matty came over to my apartment after late mass, bringing two hoagies as an offering. The first October rain had come overnight, but the sun burned through by noon and a wet world gleamed. It was the sort of day that tugs you outside. I would have liked to spend it with Laura, but she had gone home to visit her mother.

I had offered her a ride to Doylestown, but she’d insisted on taking the bus, turning a ninety-minute drive into a four-hour journey. She’d told me that her mother was sternly conservative and would need to be prepared for my debut. Entrusted with her own key—something no other girl had ever received from me—she’d promised to come straight to the apartment when she got back late Sunday night.

Matty and I sat in my living room, with me playing an acoustic guitar and Matty’s volume low as we worked on an extended song to fit the musical fashion for profundity. Our progress was slow. I worked best alone, while Matty, who dazzled me with his cascading improvisations, could not write a singable melody to save his life. His attempts at producing lyrics were even more inept. When I came up with a verse or chorus, though, he could forge marvelous bridges and haunting interludes. It gave me great satisfaction to be able to do something Matty could not, to take the lead for a change. Instead of closing the gap between my guitar skills and his invincible talent, all of my fervent practicing only left me further behind. Jealousy ebbed and flowed.

Our intended masterpiece had the working title “America: Speed Limit 90.” But we were just trading licks, waiting for inspiration, when Joey Schaeffer showed up.

“What’s happening?” he asked. He had begun to grow a beard, which was coming in full and black. “Working on the symphony again?”

“There’s half a hoagie in the fridge, if you’re hungry,” I told him.

Joey picked up the new Esquire. The two dead Kennedys and Martin Luther King had been gimmicked onto the cover, their cutout figures imposed on a field of white crosses. It was a disappointing issue. Joey quickly tossed it back atop the latest issue of Crawdaddy!

“Listen,” he said. “You guys need to go to Buzzy’s party.”

“Buzzy’s an asshole,” I said.

Matty had nothing to say.

“Yeah, he can be an asshole,” Joey admitted. He concentrated on me. “But he knows he blew it with you, man. He wants to make amends, you know? He specifically asked me to get you to come.”

“I don’t do skid row orgies without running water.”

“It’s just a regular party.”

“Come on, Joey. Why does it matter to you?”

“Buzzy and I go back, man. He helped my brother out. For what it was worth. Anyway, he just called me up and asked me if I could get you and some other guys from the band to come over. He’s a groupie at heart. Know what I mean?” He switched his effort to Matty. “Tooker’s new band is playing at the party. It’s just some dumb-Dutch hicks from Tremont and Pine Grove, kind of a downer, but Tooker really wants you to hear what he’s doing. He’s still bummed out, you know? He wants to show you he landed on his feet.”

“There’s no electricity out at the farm,” I said.

“They rented a generator. Look, Buzzy’s really sorry for being such a shit,” Joey told me. “And Tooker’s just trying to salvage a little pride. You really ought to go. It’s like, you know, noblesse oblige.”

“Buzzy still telling everybody I’m a narc?”

“He stopped that shit months ago. You were supposed to be his only anointed son, you know? You were a major defeat in Buzzy’s war on reality.”

“And I was supposed to be Frodo, so he could be Gandalf. All his Tolkien crap got really sick. If anything, Buzzy’s a two-bit Dark Lord. And his Shire’s got bad karma.”

“He’s over all that, too.”

Buzzy’s farmhouse was haunted by the walking dead. He surrounded himself with strays who more or less did his bidding. Buzzy controlled the dope and, thus, his tribe. It embarrassed me, infuriated me, that I had believed we were cosmic brothers, with Buzzy the elder. Our relationship had played out right after my father’s death.

“If you need company,” I said, “go get Frankie. He never met a party he didn’t like.”

“I already asked him. He’s stuck taking Angela to the movies. She’s got her ass up about something. And Stosh still feels funny about Tooker.”

Matty spoke up. “Tooker had no discipline. His playing wasn’t good enough.”

His tone was a revelation. Belatedly, I grasped that it hadn’t been Frankie or Stosh who fired Tooker from the band, but Matty. It gave me a passing chill to think that Matty could come home from Nam, listen to us for a few songs, and make a decision to give an old pal the boot. It didn’t square with the image I had of him being content with the universe as long as he could play music.

“Shit, why not?” I said. “Come on, Matty. It’s too nice to stay inside.”

I still didn’t want to have anything to do with Buzzy. But I wanted to see Matty and Tooker together. I wondered what else I’d been missing.

Matty shrugged. “I guess it wouldn’t hurt.”

* * *

Buzzy’s farmhouse sat in a glen at the end of a road so rutted, you had to take it at five miles per hour. That feature had been crucial to Buzzy’s selection of the property, since it meant that any police raid would offer plenty of warning, unless the cops were willing to come over the hills on foot and work down through the woods. Otherwise, the property offered only fields so barren that the Pennsylvania Dutch had abandoned them, a collapsing barn full of black snakes, and a house watered only by a hand pump in the kitchen and another in the yard. The site was lush and madly overgrown, colored now by autumn.

Joey crawled along the farm track, cursing every time a deep hole punished his Shelby Cobra. Joey wasn’t an obvious materialist, but there were two things he would have defended with his life: his Fisher stereo system and that growling black Mustang.

I sat bunched up in the back, with Matty barely contained by the bucket seat in front of me.

“I should’ve unloaded the van and brought it,” Joey said. “This is going to tear out my exhaust.”

We had the windows up to keep out the combination of mud and dust, so we didn’t hear the band until we got close. Forewarned of our approach by the Mustang’s growl, Buzzy waited in the field where everybody parked, a sovereign condescending to meet the foreign ambassadors at the edge of his kingdom.

He grinned, beaver-toothed, and shook my hand. He had enormous hands. The greasy fringe of hair on his forehead didn’t quite cover a thick array of blackheads.

In the background, an amateur band blundered through “In-A-Gadda-Da-Vida,” an endless number destined to replace “Wipe Out” as the favorite song of rubes aching to be hip. The noise from the generator was almost as loud as the music.

Leading us up toward the h

ouse through damp grass, Buzzy said, “I hear the new band’s great. The Innocence, right?”

“The Innocents.”

“Yeah, right. I hear nothing but good things about you, some heavy shit. You hear Arthur Brown yet? That is serious music.…” He adjusted his path to walk closer beside me. Our sleeves brushed. “You and I ought to make a fresh start. Let bygones be bygones. Things got crazy.”

“Still got your deer rifle?”

He grinned. The Beaver of Evil. “New Remington twelve-gauge, too. I’ve been cleaning the snakes out of the barn.”

I was tempted to make a comment about the snakes in his head. But there was no point. We were there. And I was the chimp who had agreed to come. Just bring on the memories of nausea and degradation.

Yet, something else lingered down deep. At his best, Buzzy could be charismatic, almost hypnotic. I had been impressed by his ability to quote philosophers germanely, until I discovered that he read philosophy only in search of quotes. He reminded me of Bazarov in Fathers and Sons, rich with indefinite talents and bound for a pointless end. One talent Buzzy didn’t have was musical ability. During our mutual infatuation, he had asked me to give him guitar lessons, but he’d never practiced seriously. He expected things to just come to him and resented it when they didn’t.

Tooker noted our arrival and nodded. The band was awful, not even in tune. After applause from three or four stoners for the Iron Butterfly number, they launched into an off-key version of “Incense and Peppermints,” psychedelia packaged by corporate America.

Buzzy had parties and Parties. This was a Party, with perhaps fifty visitors wandering around, a few of them tripping their brains out. Males outnumbered females four to one, and the girls looked in need of shampoo and penicillin. I did my best to avoid a would-be guitar player from Schuylkill Haven who wrote sappy songs and ate too much LSD. He wore an orange paisley shirt with a Russian collar. It made him look like a reject from The Mod Squad. I wondered if he was my replacement in King Buzzy’s court.

Several guests were drug connections with whom Buzzy had dealt during my tenure. A few were truly bad hombres, including two black dudes from Harrisburg with an overweight blonde in tow. Otherwise, the usual Buzzy crew was there, shiftless guys in their twenties who hung out at the farm for weeks when their homes became untenable. In the past, society would have classed them as bums. Now they had been promoted to hippie status, representatives of the counterculture.

The Hour of the Innocents

The Hour of the Innocents